As part of Black Swamp Bird Observatory's mission to inspire the appreciation, enjoyment, and conservation of birds and their habitats, we are extending the scope of our research to include this series of Bird Migration Profiles. With over three decades of bird banding data collected from the marshes of northwest Ohio, BSBO’s Research Department is the leading authority on songbird migration along Lake Erie. Through this robust data set (and thousands of volunteer hours), BSBO has been able to document the approximate timing of migration for numerous species, their sexes, and their ages, traveling through Ohio in spring and fall.

Based on this data, our research department has been able to generate detailed graphs displaying the peak movements of species as they pass through the region, providing an easy visualization of migration. Knowing the timing of each species is extremely useful for land managers, researchers, and birders attempting to conserve, study, and view these flying wonders. The advantage of these banding data over collected observational data is its consistency and accuracy.

Based on this data, our research department has been able to generate detailed graphs displaying the peak movements of species as they pass through the region, providing an easy visualization of migration. Knowing the timing of each species is extremely useful for land managers, researchers, and birders attempting to conserve, study, and view these flying wonders. The advantage of these banding data over collected observational data is its consistency and accuracy.

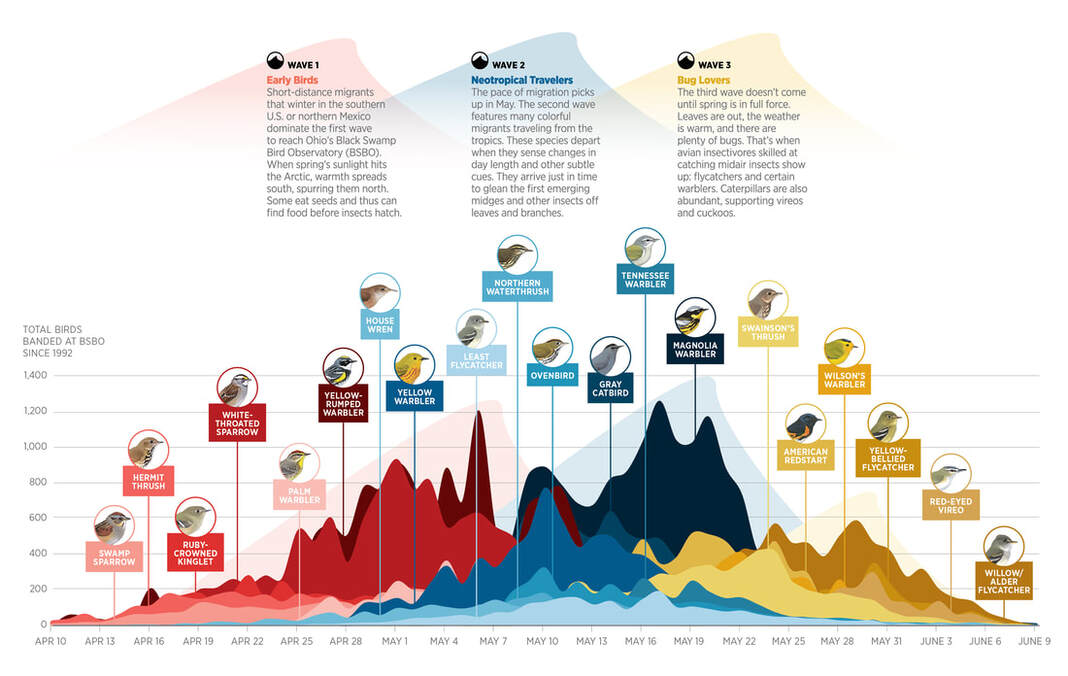

Below you’ll find the bird families that BSBO’s banding data has been able to - thus far - generate timing graphs for. Along with their timing graphs, these profiles also include identification descriptions, songs, migration habitat, and BSBO's banding numbers. While 149 species in total have been banded during BSBO's songbird research, 101 (including common subspecies) have enough data to qualify as significant. Data used to compile these profiles has also been key in developing BSBO's "Wave Theory" of spring songbird migration (found in the Information section of this page) and featured in Audubon Magazine.

Also included on this page are further readings detailing the science behind predicting migration, why Northwest Ohio and Lake Erie are hotspots for migration, BSBO's research study design, and graph interpretation.

Also included on this page are further readings detailing the science behind predicting migration, why Northwest Ohio and Lake Erie are hotspots for migration, BSBO's research study design, and graph interpretation.

Information

Research Overview

The importance of understanding avian migration and stopover habitat needs has greatly increased over the past two decades as tropical deforestation and temperate forest fragmentation have expanded and songbird populations have declined. Little information is known about the "problems" migrants contend with along their migratory routes (Morse 1980), not to mention the transition between spring migration and the breeding period. Recent studies have indicated that upwards of 80% of annual mortality occurs during migration for many landbirds (Sillett and Holmes 2002). To offset the energetic costs of migration, birds deposit substantial lipid reserves (fat) which may reach 50% of body weight among long distance intercontinental migrants (Berthold 1975). As fat is depleted during migration, birds are capable of replenishing reserves in a few days at rates approaching 10% of body weight per day (e.g. Barlein 1985; Biebach et al. 1986; Moore & Kerlinger 1987). These fat deposits are obviously critical for a successful migration, and they may also provide a selective advantage to the migrant with energy reserves remaining when they reach their breeding grounds (see Sinclair 1983; Ojanen 1984; Krapu et al. 1985; Krementz & Ankney 1987).

Annual, site, species, and weather variation are large uncontrollable parameters that cloud short-term studies. There are few long-term (greater than 20 years) programs for resource managers to utilize to inform decision making processes. These long-term datasets, such as that from the Navarre banding station, offer the greatest value in the interpretation of long-term ecological change. With continuing habitat loss along both the Lake Erie coast and inland, this study will assist in monitoring the effects of habitat isolation and degradation on use by migratory landbird species.

The tremendous increase in human interest of migrating birds has developed a vast ecotourism industry. The institution of the Biggest Week in American Birding festival a decade ago has leveraged this great interest for bird conservation in the Lake Erie Marsh Region and beyond. While providing a service to visitors to the region who wish to enjoy the spectacle of birds, this event has also brought new knowledge to the local communities of the value of wildlife and the habitats they depend upon.

This series of documents is a realization of 30 years of hard and dedicated work by many individuals, and presents results of migrational timing to increase the opportunity for bird enthusiasts to learn and improve their time spent afield.

Annual, site, species, and weather variation are large uncontrollable parameters that cloud short-term studies. There are few long-term (greater than 20 years) programs for resource managers to utilize to inform decision making processes. These long-term datasets, such as that from the Navarre banding station, offer the greatest value in the interpretation of long-term ecological change. With continuing habitat loss along both the Lake Erie coast and inland, this study will assist in monitoring the effects of habitat isolation and degradation on use by migratory landbird species.

The tremendous increase in human interest of migrating birds has developed a vast ecotourism industry. The institution of the Biggest Week in American Birding festival a decade ago has leveraged this great interest for bird conservation in the Lake Erie Marsh Region and beyond. While providing a service to visitors to the region who wish to enjoy the spectacle of birds, this event has also brought new knowledge to the local communities of the value of wildlife and the habitats they depend upon.

This series of documents is a realization of 30 years of hard and dedicated work by many individuals, and presents results of migrational timing to increase the opportunity for bird enthusiasts to learn and improve their time spent afield.

Lake Erie Songbird Migration

Why is the Lake Erie Marsh Region the “Warbler Capital of the World”? Location, location, location. Lake Erie represents a barrier to most passerine migrants. Passerines' reluctance to navigate open water results in major concentrations along the southwestern shore of Lake Erie, unparalleled in the Midwest.

A large east-west body of water induces confusion in many species of migratory bird. This confusion results in hesitation and decision making: Does the bird continue onward, does it descend to the ground, does it veer in another direction? All viable options, all of them used. Many factors combine to make these choices. Some right, some wrong for the individual, but ultimately right for the species. It is all part of what is known as lake effect. Lake Erie is not the first barrier for many and if lucky, won’t be the last.

For the vast number of species, the driver of migration is ingrained in their very DNA. This driver is different in the spring for males and females and in fall for adults and young. Day length - microseconds worth - creates the stimulus that sets off the sequence of events known as “zugunruhe” and initiates the eons old migration. This "migratory restlessness" culminates in the behaviors we witness during this great spectacle each spring and fall.

For spring migration, circumstances are much more defined. The motivation of every bird is to move north to a breeding habitat and carry on the species' survival. Each species has a predetermined timing, each with considerable variation among individuals, an important component in species long-term existence. This driver, day length, is acted on by many outside influences, most notably weather. Weather “tweaks” migration, resulting in annual variation of first arrival dates and species peaks from year to year. The “swallows of Capistrano” and “buzzards of Hinkley” are myths, but based on some fact. The intricacies of how weather affects migration is covered in the section Wave Theory.

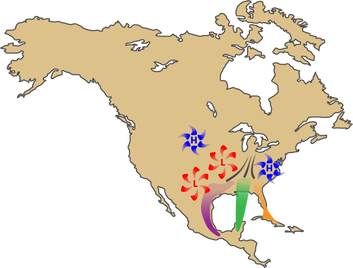

Let’s revisit why this region is the “Warbler Capital of the World." Neotropical migrants moving northward come through three primary avenues of migration, passage through the Caribbean islands, trans-Gulf of Mexico migration from the Yucatan, and circumvention through Mexico around the west side of the Gulf. These three avenues all eventually coalesce in the Lake Erie Marsh Region, resulting in huge numbers and diverse speciation. So, this large, diverse speciation - driven by day length and moderated by weather - arrives at the greatest barrier since the Gulf itself. Here individuals make decisions that often delay their quest north.

There are only four small segments of beach ridge habitat remaining west of Port Clinton along Ohio’s Lake Erie shoreline. The intensive bird use of these ridges in contrast to the adjacent condominium complexes and marinas signifies the importance of this habitat component in the Lake Erie marsh system. A wide range of migration corridor and stopover habitat occurs throughout the region (Ewert et al. 2006), but these sites do not contain bird concentrations as high as the beach ridges. Hence, the mecca recognized worldwide: Magee Marsh State Wildlife Area and the surrounding wetland and woodland habitats.

The fall appears to paint a different picture, with habitat farther from the lake receiving much greater use. Again, DNA, day length, and weather are the major players. But now, instead of male/female driven behavior and fine-tuned breeding realities, movement is altered by age, molt requirements, and body condition. The lake is a great player as well but this time it is a barrier stopping birds on the Canadian shoreline. This affects crossing from the species level to that of individual birds. Habitat we provide is also different as many lake crossers don’t just “drop-out” with land in sight, but glide down for dozens of miles into the interior of the marsh region. Some species - such as most of the flycatchers - seem to “circumvent” the lake just as they do the Gulf in the spring, and the numbers of encounters reflect the variation.

The location, the habitat, and bird behavior all work together to create what we have come to recognize as one of the real spectacles of the natural world. See the Wave Theory and the Research Study Design sections to get a better understanding of why and how we have arrived at the development of these Species Migration Profiles and how better to use their contribution to your enjoyment of birds.

A large east-west body of water induces confusion in many species of migratory bird. This confusion results in hesitation and decision making: Does the bird continue onward, does it descend to the ground, does it veer in another direction? All viable options, all of them used. Many factors combine to make these choices. Some right, some wrong for the individual, but ultimately right for the species. It is all part of what is known as lake effect. Lake Erie is not the first barrier for many and if lucky, won’t be the last.

For the vast number of species, the driver of migration is ingrained in their very DNA. This driver is different in the spring for males and females and in fall for adults and young. Day length - microseconds worth - creates the stimulus that sets off the sequence of events known as “zugunruhe” and initiates the eons old migration. This "migratory restlessness" culminates in the behaviors we witness during this great spectacle each spring and fall.

For spring migration, circumstances are much more defined. The motivation of every bird is to move north to a breeding habitat and carry on the species' survival. Each species has a predetermined timing, each with considerable variation among individuals, an important component in species long-term existence. This driver, day length, is acted on by many outside influences, most notably weather. Weather “tweaks” migration, resulting in annual variation of first arrival dates and species peaks from year to year. The “swallows of Capistrano” and “buzzards of Hinkley” are myths, but based on some fact. The intricacies of how weather affects migration is covered in the section Wave Theory.

Let’s revisit why this region is the “Warbler Capital of the World." Neotropical migrants moving northward come through three primary avenues of migration, passage through the Caribbean islands, trans-Gulf of Mexico migration from the Yucatan, and circumvention through Mexico around the west side of the Gulf. These three avenues all eventually coalesce in the Lake Erie Marsh Region, resulting in huge numbers and diverse speciation. So, this large, diverse speciation - driven by day length and moderated by weather - arrives at the greatest barrier since the Gulf itself. Here individuals make decisions that often delay their quest north.

There are only four small segments of beach ridge habitat remaining west of Port Clinton along Ohio’s Lake Erie shoreline. The intensive bird use of these ridges in contrast to the adjacent condominium complexes and marinas signifies the importance of this habitat component in the Lake Erie marsh system. A wide range of migration corridor and stopover habitat occurs throughout the region (Ewert et al. 2006), but these sites do not contain bird concentrations as high as the beach ridges. Hence, the mecca recognized worldwide: Magee Marsh State Wildlife Area and the surrounding wetland and woodland habitats.

The fall appears to paint a different picture, with habitat farther from the lake receiving much greater use. Again, DNA, day length, and weather are the major players. But now, instead of male/female driven behavior and fine-tuned breeding realities, movement is altered by age, molt requirements, and body condition. The lake is a great player as well but this time it is a barrier stopping birds on the Canadian shoreline. This affects crossing from the species level to that of individual birds. Habitat we provide is also different as many lake crossers don’t just “drop-out” with land in sight, but glide down for dozens of miles into the interior of the marsh region. Some species - such as most of the flycatchers - seem to “circumvent” the lake just as they do the Gulf in the spring, and the numbers of encounters reflect the variation.

The location, the habitat, and bird behavior all work together to create what we have come to recognize as one of the real spectacles of the natural world. See the Wave Theory and the Research Study Design sections to get a better understanding of why and how we have arrived at the development of these Species Migration Profiles and how better to use their contribution to your enjoyment of birds.

Wave Theory

The section labeled Lake Erie Migration delves into the habitat and the circumstances that have made the Marsh region the important stopover site that it is. The structure of our research will be explained in detail in the section Research Study Design. In this Wave Theory section we will lay out the fine details of the movements of birds and what you can do to predict their anticipated coming each spring. The research is precise enough to expand your joy of birds and even to predict your own health; more on that later.

The embedded DNA coding in each species provides the road map for migration timing and pathway. Weather provides the variability, the assistance, and the detriment to this extremely costly endeavor known as bird migration.

The embedded DNA coding in each species provides the road map for migration timing and pathway. Weather provides the variability, the assistance, and the detriment to this extremely costly endeavor known as bird migration.

|

First, we must understand the generalities of how weather works. The premise is that weather systems generally cross the continent entering off the California coast and moving eastward and exiting the east coast. The big players in favorable migration are the low-pressure cells. Generally, it takes about seven days for a low arriving along the California coast to cross the country. When this low-pressure cell is in the Oklahoma/Arkansas region it sets up the potential for favorable migration in the eastern part of the country. Warm fronts that rotate counter-clockwise off the low collect tropical winds from the Gulf and send them up the Mississippi and Ohio river valleys, ultimately to the shores of Lake Erie. Migrant birds ride these fronts, often pushing just ahead of or trailing the front on southwest winds that reduce the cost of flight. Associated with these warm fronts and low pressure is the ever presence of precipitation and heavy storms, that while providing the favorable winds also increase risk of inclement weather. |

There is variation in the way these weather patterns traverse the continent. Many factors including the jet stream, polar vortexes, and Pacific Ocean eruptions of El Nino and La Nina events affect the behavior of the weather patterns. A common effect is the pulling of the low-pressure cell from the usual trajectory into the Great Lakes. This is often associated with the Pacific events and results in the warm fronts collecting Pacific winds from the west rather than tropical Gulf winds. For the Marsh Region, the results are springs of good speciation but lower numbers of birds as they are spread out along a longer frontal boundary.

Short-distance migrants wintering within the continental United States and neotropical migrants from Central and South America are all affected by these weather patterns, but often very differently. Short-distance migrants are generally early migrant movers and are heavily affected by weather patterns across the eastern US. As a result, they have considerable variability in their timing as warm weather can cause early movement. Birds wintering south of the border have no idea we are under warm conditions and are not pulled from normal behavior.

|

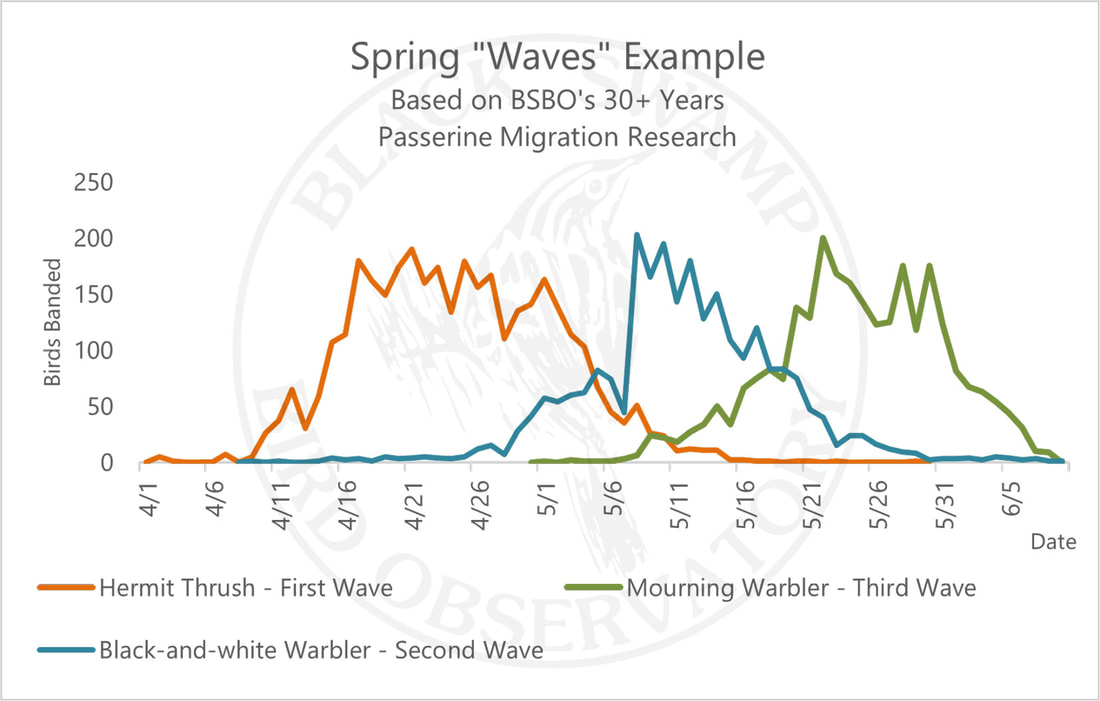

Through our research, we have found that large numbers of Neotropical migrants arrive in three “waves”, each of which has two pulses along the south coast of Lake Erie. These “pulses” are usually about seven days apart (the time it takes for a pressure cell to cross). The first wave is dominated by male White-throated Sparrow, Hermit Thrush, male (Myrtle) Yellow-rumped Warbler, and male Ruby-crowned Kinglet, and occurs around 24 April. This wave is known as the “overflight” wave as a series of more southern warblers which are early migrants get caught up in the favorable winds and “over-fly” their normal range. |

The second wave occurs 07-13 May and is represented by the greatest species diversity of the spring. It is dominated by female White-throated Sparrow, Swainson’s Thrush, female (Myrtle) Yellow-rumped Warbler, female Ruby-crowned Kinglet, and male Magnolia Warbler. A second pulse of this wave comes five to seven days later, usually has the largest volume, but contains the same dominant species. The third wave normally comes around Memorial Day weekend and is dominated by female Magnolia Warbler, American Redstart, Mourning Warbler, vireos, and flycatchers with a second pulse in the first few days of June.

Once the first wave hits, it becomes fairly predictable to estimate migration timing. This is where we come back to birds helping you predict your own health. While it is easy to propose that getting out and enjoying birds is good for one’s health, if you watch the weather reports, follow the low pressures crossing the country, and pick up on a cells’ entry off California, you have an advantage knowing that it should take about three days to reach Oklahoma. So, you have about three days to determine your malady and inform the bosses of when you will be “sick” and need a day of R&R. You can predict your own health!

Once the first wave hits, it becomes fairly predictable to estimate migration timing. This is where we come back to birds helping you predict your own health. While it is easy to propose that getting out and enjoying birds is good for one’s health, if you watch the weather reports, follow the low pressures crossing the country, and pick up on a cells’ entry off California, you have an advantage knowing that it should take about three days to reach Oklahoma. So, you have about three days to determine your malady and inform the bosses of when you will be “sick” and need a day of R&R. You can predict your own health!

Research Study Design

The specific goals of the project are to monitor the population status of Neotropical migrants in the Great Lakes region and to better understand the relationship between en-route habitat and their breeding and winter ecology in order to inform conservation decisions that protect these species throughout the entire life cycle.

Adequate stopover habitat may play an important role in delivering migrating passerines to their breeding grounds with sufficient energy reserves to successfully nest. In addition to the biological stressors confronting migratory birds, the changing landscape presents increasing risks of human-induced mortality and individual and population stressors.

The primary bird banding site operated by Black Swamp Observatory is located at the Navarre Unit of Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge. It sits on the largest remaining beach ridge along the western basin of Lake Erie, and holds the most complete native beach ridge vegetative complex. Habitat at the site is dominated by Carolinian forest with multiple bands of wetland associations. Hackberry and Kentucky Coffeetree along with Eastern Cottonwood and White Ash make up the majority of the overstory. The understory is primarily several species of Dogwood, Buttonbush, and Bush Honeysuckle. Herbaceous layers include a wide variety of herbs, sedges, and grasses. There is a diverse wildflower component but considerable damage from invasive Garlic Mustard and overgrazing by White-tailed Deer are stressors to this layer.

Banding effort covers a minimum of 75% of the migration period for the study site. Every attempt was made to equalize any un-sampled parts of the migration period at the beginning and ending of that time frame. The migration period covers both short-distance and long-distance (neotropical) migrants.

Placement of mist nets is designed to represent the habitat at the site and to bisect primary bird movement direction and corridors. Mist nets are considered a random method of capture with the premise being they are undetectable by foraging and traveling birds. This is a broad assumption with many caveats that must be considered in data analysis. In reality, not all birds have equal chance of capture. Bird size affects the chances of being captured and held in the net, species behavior can be a factor across species, height of activity is a factor, and weather effects can occur on any given day.

Mist netting was conducted from one-half hour before sunrise to at least 11:00 AM on each day of operation, weather permitting. Birds were captured utilizing 2.6 x 12 meter mist nets of 30mm mesh size. All birds were removed from the net and placed in a mesh holding bag until processing. During processing, each bird was banded with a standard U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service leg band, measured by closed wing chord, body mass recorded, visually inspected for subcutaneous fat deposits using a 13-point ordinal scale (based on Helms & Drury 1960), and time stamped to net round. Birds were sexed and aged by the use of plumage characteristics (Pyle 1997) and guidelines of the Bird Banding Manual and Woods Manual (Woods 1969).

Although not incorporated within these profiles, point counts were performed for every day of banding operations, providing another data set to augment banding data. These point count data provide further insight into the movements of species that are highly mobile but experience relatively low capture rates (e.g. Blue Jay and Tree Swallow) or are outside of the range of capture (due to behavior) or ability to be captured (due to size) (e.g. raptors, waterfowl, gulls).

Adequate stopover habitat may play an important role in delivering migrating passerines to their breeding grounds with sufficient energy reserves to successfully nest. In addition to the biological stressors confronting migratory birds, the changing landscape presents increasing risks of human-induced mortality and individual and population stressors.

The primary bird banding site operated by Black Swamp Observatory is located at the Navarre Unit of Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge. It sits on the largest remaining beach ridge along the western basin of Lake Erie, and holds the most complete native beach ridge vegetative complex. Habitat at the site is dominated by Carolinian forest with multiple bands of wetland associations. Hackberry and Kentucky Coffeetree along with Eastern Cottonwood and White Ash make up the majority of the overstory. The understory is primarily several species of Dogwood, Buttonbush, and Bush Honeysuckle. Herbaceous layers include a wide variety of herbs, sedges, and grasses. There is a diverse wildflower component but considerable damage from invasive Garlic Mustard and overgrazing by White-tailed Deer are stressors to this layer.

Banding effort covers a minimum of 75% of the migration period for the study site. Every attempt was made to equalize any un-sampled parts of the migration period at the beginning and ending of that time frame. The migration period covers both short-distance and long-distance (neotropical) migrants.

Placement of mist nets is designed to represent the habitat at the site and to bisect primary bird movement direction and corridors. Mist nets are considered a random method of capture with the premise being they are undetectable by foraging and traveling birds. This is a broad assumption with many caveats that must be considered in data analysis. In reality, not all birds have equal chance of capture. Bird size affects the chances of being captured and held in the net, species behavior can be a factor across species, height of activity is a factor, and weather effects can occur on any given day.

Mist netting was conducted from one-half hour before sunrise to at least 11:00 AM on each day of operation, weather permitting. Birds were captured utilizing 2.6 x 12 meter mist nets of 30mm mesh size. All birds were removed from the net and placed in a mesh holding bag until processing. During processing, each bird was banded with a standard U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service leg band, measured by closed wing chord, body mass recorded, visually inspected for subcutaneous fat deposits using a 13-point ordinal scale (based on Helms & Drury 1960), and time stamped to net round. Birds were sexed and aged by the use of plumage characteristics (Pyle 1997) and guidelines of the Bird Banding Manual and Woods Manual (Woods 1969).

Although not incorporated within these profiles, point counts were performed for every day of banding operations, providing another data set to augment banding data. These point count data provide further insight into the movements of species that are highly mobile but experience relatively low capture rates (e.g. Blue Jay and Tree Swallow) or are outside of the range of capture (due to behavior) or ability to be captured (due to size) (e.g. raptors, waterfowl, gulls).

Timing Graph Information

Species graphs are based on BSBO’s long-term (30+ years) research banding data from its passerine migration monitoring station. For each species, birds banded have been totaled across years for each respective day, emphasizing the consistency of their movements annually. Through graphs such as these, BSBO has been able to detail the “wave” theory of passerine migration, identifying major movements of birds that occur roughly the same time each year.

The benchmark for a species' inclusion was at least 30 individuals banded in either the spring or fall during the entirety of BSBO's research project, for an average of at least one bird per year. This criterion was also used for the inclusion of sexes and ages. So, while BSBO has encountered Nelson's Sparrow, Swainson's Warbler, and Bicknell's Thrush during its banding history, the handful of individuals of these species do little to convey the whole species' migrational timing.

The x-axis/horizontal displays the date of migration and the y-axis/vertical represents the cumulative number of birds banded. Total birds banded is populated for every graph, and if adequate data are available, males and females are displayed, as are adult and young, and the central 25%-75% of birds banded representing the core of the species’ movement (i.e. the time when the bulk of the species is present). Though a species’ migration occurs approximately the same time every year, weather does affect the actual arrival date. Highlighting the dates of this central range allows for the slight variance that occurs each year. In most cases with a typical bell curve, this highlighted section encompasses the peak movement of the species. However, with some of the more resident species and some instances in fall, peaks may actually occur outside of this range due to a prolonged migration with either initial or end spikes of movement.

In spring, adult males of a species tend to arrive in the area first and show the first major spike on a graph. Young males followed shortly by adult females are the next to arrive in big numbers and add to the core peak of birds. Lastly, young females arrive, contributing to a third (but much smaller) peak as the species’ migration winds down.

The benchmark for a species' inclusion was at least 30 individuals banded in either the spring or fall during the entirety of BSBO's research project, for an average of at least one bird per year. This criterion was also used for the inclusion of sexes and ages. So, while BSBO has encountered Nelson's Sparrow, Swainson's Warbler, and Bicknell's Thrush during its banding history, the handful of individuals of these species do little to convey the whole species' migrational timing.

The x-axis/horizontal displays the date of migration and the y-axis/vertical represents the cumulative number of birds banded. Total birds banded is populated for every graph, and if adequate data are available, males and females are displayed, as are adult and young, and the central 25%-75% of birds banded representing the core of the species’ movement (i.e. the time when the bulk of the species is present). Though a species’ migration occurs approximately the same time every year, weather does affect the actual arrival date. Highlighting the dates of this central range allows for the slight variance that occurs each year. In most cases with a typical bell curve, this highlighted section encompasses the peak movement of the species. However, with some of the more resident species and some instances in fall, peaks may actually occur outside of this range due to a prolonged migration with either initial or end spikes of movement.

In spring, adult males of a species tend to arrive in the area first and show the first major spike on a graph. Young males followed shortly by adult females are the next to arrive in big numbers and add to the core peak of birds. Lastly, young females arrive, contributing to a third (but much smaller) peak as the species’ migration winds down.

Literature Cited

Barlein, Franz 1985. Efficiency of food utilization during fat deposition in the long distance migratory garden warbler, Sylvia borin. Oecologia 68:118-125.

Berthold, P. 1975. Migration: control and metabolic physiology. Pp. 77-128. In: Avian Biology, D.S. Farner and J.R. King (eds). vol 5. Academic Press: New York.

Biebach, H., W. Friedrich, and G. Heine. 1986. Interaction of body mass, fat, foraging and stopover period in trans-Sahara migrating passerine birds. Oecologia 69:370-379.

Ewert, D.N., G.J. Soulliere, R.D. Macleod, M.C. Shieldcastle, P.G. Rodewald, E. Fujimura, J. Shieldcastle, and R.J. Gates. 2006. Migratory bird stopover site attributes in the western Lake Erie basin. Final report, George Gund Foundation.

Helms, C.W. and W.H. Drury. 1960. Winter and migratory weight and fat field studies on some North American buntings. Bird Banding 31: 1-40.

Krapu, G.L., G.C. Iverson, K.J. Reinecke, and C.M. Boise. 1985. Fat deposition and usage by arctic-nesting Sandhill Cranes during spring. Auk 102: 362-368.

Krementz, D.G. and C.D. Ankney. 1987. Changes in lipid and protein reserves and in diet of breeding House Sparrows. Can. J. Zool. 66: 950-955.

Moore, F. and P. Kerlinger. 1987. Stopover and fat deposition by North American wood-warblers (Parulinae) following spring migration over the Gulf of Mexico. Oecologia 74: 47-54.

Morse, D.H. 1980. Population limitations: breeding or wintering grounds? In: Migrant birds in the Neotropics (A. Keast and E.S. Morton, eds.), Smithsonian Press, Washington, D.C. Pp. 505516.

Ojanen, M. 1984. The relation between spring migration and the onset of breeding in the Pied Flycatchers Ficedula hypoleuca in northern Finland. Ann. Zool. Fennici 21: 205-208.

Pyle, Peter. 1997. Identification guide to North American birds. Part I. Slate Creek Press, Bolinas, CA. 731 pp.

Sillett, T.S. and R.T. Holmes. 2002. Variation in survivorship of a migratory songbird throughout its annual cycle. Journal of Animal Ecology 71:296-308.

Sinclair, A.R.E. 1983. The function of distance movements in vertebrates. In: The Ecology of Animal Movement. I.R. Swingland and P.R. Greenwood (eds). Pp. 240-258.

Wood, Merrill. 1969. A bird-banders guide to determination of age and sex of selected species. College of Agriculture, Pennsylvania State Univ., University Park, Pennsylvania.

Berthold, P. 1975. Migration: control and metabolic physiology. Pp. 77-128. In: Avian Biology, D.S. Farner and J.R. King (eds). vol 5. Academic Press: New York.

Biebach, H., W. Friedrich, and G. Heine. 1986. Interaction of body mass, fat, foraging and stopover period in trans-Sahara migrating passerine birds. Oecologia 69:370-379.

Ewert, D.N., G.J. Soulliere, R.D. Macleod, M.C. Shieldcastle, P.G. Rodewald, E. Fujimura, J. Shieldcastle, and R.J. Gates. 2006. Migratory bird stopover site attributes in the western Lake Erie basin. Final report, George Gund Foundation.

Helms, C.W. and W.H. Drury. 1960. Winter and migratory weight and fat field studies on some North American buntings. Bird Banding 31: 1-40.

Krapu, G.L., G.C. Iverson, K.J. Reinecke, and C.M. Boise. 1985. Fat deposition and usage by arctic-nesting Sandhill Cranes during spring. Auk 102: 362-368.

Krementz, D.G. and C.D. Ankney. 1987. Changes in lipid and protein reserves and in diet of breeding House Sparrows. Can. J. Zool. 66: 950-955.

Moore, F. and P. Kerlinger. 1987. Stopover and fat deposition by North American wood-warblers (Parulinae) following spring migration over the Gulf of Mexico. Oecologia 74: 47-54.

Morse, D.H. 1980. Population limitations: breeding or wintering grounds? In: Migrant birds in the Neotropics (A. Keast and E.S. Morton, eds.), Smithsonian Press, Washington, D.C. Pp. 505516.

Ojanen, M. 1984. The relation between spring migration and the onset of breeding in the Pied Flycatchers Ficedula hypoleuca in northern Finland. Ann. Zool. Fennici 21: 205-208.

Pyle, Peter. 1997. Identification guide to North American birds. Part I. Slate Creek Press, Bolinas, CA. 731 pp.

Sillett, T.S. and R.T. Holmes. 2002. Variation in survivorship of a migratory songbird throughout its annual cycle. Journal of Animal Ecology 71:296-308.

Sinclair, A.R.E. 1983. The function of distance movements in vertebrates. In: The Ecology of Animal Movement. I.R. Swingland and P.R. Greenwood (eds). Pp. 240-258.

Wood, Merrill. 1969. A bird-banders guide to determination of age and sex of selected species. College of Agriculture, Pennsylvania State Univ., University Park, Pennsylvania.