Enjoying our blogs?Your support helps BSBO continue to develop and deliver educational content throughout the year.

|

|

As we enter June, birds from here all the way to the Arctic are starting to nest or are already raising young. Migration, a phenomenon that starts in February with raptors and waterfowl, ends in early June with the last of the landbirds and shorebirds heading north through the mid-continent. For many, now is a transition time of changing from migrant birds to those breeding, and even switching to non-avian interests such as butterflies or dragonflies. For others, it is a time to reflect on the past few months of excitement and dream of the great southward migration of fall. But there is a unique migration that is ramping up in late May and will be gone by mid-June. It is a migration that goes unrecognized by most, even though it is so obvious around them. A migration that is part of the life cycle of many species of bird and is of evolutionary significance to their survival. While exhibited by many species, maybe the best example of this migration in the mid-continent region of North America is that taken on by a bird thought to be extinct as little as 75 years ago but is one of today’s most recognized birds: the Giant Canada Goose, the Canada Goose subspecies of temperate North America. This unseen, or at least unrecognized, migration by this common species is the Molt Migration of non-breeding individuals. Most people that have been out and about over the last couple of weeks may have noticed the flocks of geese that seem to have materialized out of thin air. We have seen the pairs defiantly raising broods since late April, so where have these new flocks come from and why did they become suddenly abundant? These are the two-year-olds (birds hatched last calendar year) with a few failed breeders mixed in. The Giant Canada Goose does not breed until three years old in most cases. In an evolutionary sense, these individuals could become a burden on the breeders of their species and compete for food resources against growing youngsters. So, it is in the best interest of the species, or in this case the subspecies, for these individuals to leave the breeding grounds and travel elsewhere for the important “summer molt” period. That is what these flocks of geese represent. This “cohort” of the population is staging in preparation to migrate north to molt. So they will disappear and we Midwesterners will be back to just pairs and rapidly growing goslings passing through their own ugly duckling stage. The end points of this molt migration are as traditional as the more known spring and fall grand migrations taken on by a host of species. Just as a Bald Eagle, Pectoral Sandpiper, Common Loon, Blackpoll Warbler, Song Sparrow, hen Northern Pintail, or Interior Canada Goose return to their breeding grounds, these molt migrant Giants repeatedly return to their population’s ancestral molting grounds (Teaser: notice I said hen Pintail; some cool things go on with ducks that are very different than geese and play a major role with speciation and sub-speciation, but that’s a story for another time). From band recoveries and, even more importantly, from additional auxiliary markers such as neck collars and radio transmitters, we have determined some of these traditional molt destinations. It can be very specific and fascinating. For Ohio, Giant Canadas raised in the central portion of the state (influenced by the Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area population) have the west shore of James Bay as the dominant summer molt destination. To the Ohio Giant population, it is immaterial that this happens to be the breeding grounds for the Southern James Bay population of the Interior Canada Goose. To the Interior, it’s potentially a different story, especially if habitat loss reaches the subarctic and competition becomes a problem.  Molt migrant Canada Geese from midwestern states were encountered throughout the James Bay lowlands during banding operations of the Interior Canada Goose populations that breed in this subarctic region. Molt migrant Canada Geese from midwestern states were encountered throughout the James Bay lowlands during banding operations of the Interior Canada Goose populations that breed in this subarctic region. Northeast Ohio Giants head to the… northeast, causing some of Toronto’s headaches of fouled beaches and the like. Mercer County-influenced populations from western Ohio seem to home into the western shore of Hudson Bay and into Manitoba Province. The Lake Erie Marsh region population of Magee and Ottawa NWR is a bit of a mystery as no large concentration has been discovered, but perhaps they cover the landscape of northern portions of Ontario. Michigan studies indicated a movement from breeding grounds in Michigan to the Ungava Peninsula of Quebec where James and Hudson Bays link. Regardless, come October and November, these molt migrants will return to their home breeding areas to begin the next phase of their lives. If nature isn’t fascinating enough, the Giant Canada Goose is just one example of a myriad of stories on how birds and all wildlife cope with survival both day-to-day and through generations. This is just scratching the surface of “Molt Migration” as it represents the strategy by delayed breeding species. Another form of “Molt Migration” occurs in species where the male takes little part in raising the young (ducks, for example). After breeding with the female, behavior and hormones slowly change in the male, often triggering a molt migration to a far-off land to go through the drastic molt that ducks endure each summer where they become flightless for a period as new flight feathers grow. Again, through molt migration, they cease to be a burden on the female and growing youngsters. Examples in northwest Ohio are the large flocks of male Mallards that migrate in late summer to the Lake Erie Marsh Region annually to molt. Another example is large flocks of Northern Pintail males that move to the shores of James Bay to molt, a long way from the prairies where they breed. SO, now when you see those flocks of Canada Geese in late May, think and dream about what far-off lands they will soon be heading to to retire last year’s coat of feathers. Birds are so fascinating in so many ways!

0 Comments

As we looked at the forecast in preparation to wrap up our fall banding season, Saturday, November 4th, looked like it would be the perfect day to close: warm, the lightest of breezes, and sunny skies to ensure that we were putting away dry nets. But, when Saturday morning came around, we woke up to clouds and drizzle. It mostly stopped sprinkling…and then it started again…and then it stopped again. The rain was light and intermittent enough that we still opened the nets to see what we could get, but it definitely wasn’t the day that we had hoped for. “This is awful,” we moaned. “All we wanted was one American Tree Sparrow to really make it feel like winter and the end of the season.” Well, we never did catch a tree sparrow, but…we caught a NORTHERN SHRIKE!!! Only the second Northern Shrike ever caught at the station (the other one was caught in 2007), this is a bird that really deserves the capital letters and all the exclamation points. Although there are 33 shrike species worldwide, only two of them reside in North America: Loggerhead Shrike (LOSH) and Northern Shrike (NSHR). The two look very similar, but, along with other subtle plumage differences, NSHR has a narrower black mask that usually doesn’t cover the top of the eye or the top of the bill, unlike the wider mask of the LOSH. While LOSH breed in the southern United States, NSHR breed in the Arctic and only come down to the upper U.S. over the winter, so it’s not super common to see them. But, boy, are we glad this one came to visit! Having only seen shrikes from a distance before, we were surprised by how large they actually are, about the size of a robin. They’ve also got rather chunky heads, sort of reminiscent of a parrot, although they’re more closely related to ravens and crows. And, as some of us can now personally attest to, they’ve got very sharp beaks! Like falcons and hawks, shrikes have a special feature on their beaks: a projection known as a tomial tooth that aids them in capturing and killing their prey. Seems a little vicious for a songbird, right? Except shrikes aren’t your average songbird… If you only know one fact about shrikes, it’s probably this one (and if you know nothing at all about shrikes, you might be in for a shock!): Both LOSH and NSHR are carnivorous songbirds and are known as “butcherbirds” for their habit of impaling their prey on spikes. I know we’re well past October now, but, since we caught our shrike just a couple of days after Halloween, it was pretty seasonally appropriate! Although they do eat insects, such as grasshoppers and bees, NSHR will also eat small birds and rodents and are capable of taking down prey that is just as large as they are, like robins. When taking down larger animals, they’ll bite the neck and use their tomial tooth to pinch the spinal cord, then they’ll shake their head back and forth to break the neck. Often, they’ll then impale their prey on either a natural spike, such as a hawthorn, or on barbed wire, creating a cache or a “larder.” This serves a couple of purposes: One is that, for insects that are poisonous, leaving the insect for a few days allows the toxins to break down so that it can be safely eaten. Another is that shrikes have a tendency to kill more than they need, so they have extra for days when hunting isn’t as successful. (I won’t include any impalements in this post, but if you’re curious, just Google “shrike larder,” and you’ll find plenty of photos.)

On a lighter note, some other fun facts about shrikes are that they’ll often hover like a kestrel while hunting, and they can actually mimic other birds’ calls. Additionally, when nesting, the NSHR builds such a deep cup nest that sometimes all that can be seen of the incubating female is the tip of her tail. And finally (sorry, back to impalement!), young shrikes practice their impaling skills on leaves, which is really pretty cute and can be seen in this video: https://www.audubon.org/news/watch-new-shrike-film-shows-previously-undocumented-butcher-bird-behaviors. This was an atypical fall season in many ways, not the least of which was having to close for several days due to the ridiculously cold weather. However, we all decided that, after catching a shrike, we really couldn’t complain! We couldn’t have ended the season on a better note than getting to see this wintry visitor up close, and those of us who got nipped by it will wear their scars with pride. One of the most striking birds to be encountered in wetlands, the golden-fronted Prothonotary Warbler (PROW) captures the attention of anyone who catches a glimpse of these glittering inhabitants of forested swamps. To better understand their relationship with the marshes of northwest Ohio, BSBO has been fitting PROW with nanotag radio trackers since 2021, following their movements in spring and summer by utilizing the Motus network of automated radio telemetry towers (read more about that project HERE). To complement that study and learn more about the dispersal of birds following the breeding season, our research team is beginning a new fall project to mark traveling PROW, and we could use your help! Just as we've documented an increasing trend of PROW at our Navarre Marsh banding station in the spring, we've also noticed this same trend in fall. To document these birds following their departure from our banding station, we are now outfitting fall birds with a color band in addition to their federal aluminum band. It's hoped that one of these birds may be spotted during its southern migration, standing out better in binoculars and photos with a green band. But the highest chances for encounters will come next spring when these birds return to the marshes to breed, along with the thousands of birders and photographers visiting the region during spring migration.

If you happen across one of these green marked PROWs, let us know! The best documentation is with a camera, but if you spot one of our banded PROWs, please email [email protected] with the date of the sighting, the location, the color combination, and a photo (preferable). While it would be great to get a photo of the federal band and its number, this isn't always possible to accomplish. But a photo with the combination of green and silver will at least let us know whether the bird was banded as an adult (green above silver) or a young of the year (silver above green). We look forward to hearing from you soon as we try to learn more about this shimmering species. When spring migration comes to a close, we at Black Swamp Bird Observatory quickly switch gears and begin new banding endeavors. Summer is when we transition over to a different program called MAPS, or Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship, which focuses on breeding birds. MAPS is a continent-wide banding scheme where stations throughout the country all follow the same protocol to collect data on the birds that breed in their area. The breeding season is separated into ten-day periods, and banding occurs on one day during each of those periods. BSBO runs two MAPS stations: one at the BSBO office in Magee Marsh and one in Oak Openings Preserve Metropark. We all have sort of a love-hate relationship with MAPS; it’s great to get to work with a different suite of birds than we see at our migration station in the Navarre Marsh unit of Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge, and it’s so much fun when we start to catch baby birds, but it’s also usually ridiculously hot and filled with mosquitoes, deerflies, ticks, and chiggers…so it can be a little unpleasant. But throughout the summer season, we lucked out most days with biting insects and the weather. Our first day at Oak Openings in June was probably the coldest day we’ve ever had out there, and we actually managed to stay in long sleeves for the entire morning. The bugs weren't too bad, either, although the deerflies at BSBO started to pick up at the end, and some of us are bug magnets… MAPS banding is a very different feel than migration banding in that it’s usually a lot slower. If we catch 45 birds at Navarre, it’s a pretty slow day, but 45 birds at MAPS is a REALLY good day! This is mostly because, since the birds are breeding, they’re not moving around as much. They’re either sitting on the nest or foraging, and because there are lots of insects around, they don’t have to fly far to find food. Numbers may pick up when the young start to fledge, but, until then, we get a fair amount of downtime in the mornings. That being said, we’ve had some pretty exciting moments this summer, mostly at our Oak Openings site. One of those moments had to do with a bird that we didn’t even capture! We’d heard reports of a Mississippi Kite (MIKI) in the region and thought we might go looking for it after we’d finished banding. But, luckily for us, while we were going through our checklist of observed species at the end of the morning, we saw what we first thought was a hawk flying overhead…but it was the kite! We got a pretty good look (although not good photos…) before it flew away. As you might guess from the name “Mississippi” Kite, this elegant raptor is a southern bird, very unusual this far north. Not only was this bird a lifer for all of us, but we got to add a new bird to the Oak Openings list! One of our favorite birds at the Oaks station is the Red-headed Woodpecker (RHWO). Most years, we only catch one of these noisy birds, maybe two, if we’re lucky. This year we ended up with three! Two of them were caught in the same net at the same time, making it likely that they’re a breeding pair, but, since we can’t sex them, we can’t say for sure. RHWO are not sexually dimorphic, meaning that the male and female look exactly the same. Some birds that are impossible to sex by plumage are still able to be sexed during the breeding season because of their breeding characteristics: a cloacal protuberance (CP) means it’s a male, and a brood patch (BP) means it’s a female. However, in some species (often cavity nesters), the males help incubate the eggs, so they develop a brood patch, as well. This is the case for RHWO, and the males also don’t develop a CP, so there’s no way to sex them at all. Male or female, though, they’re just such handsome birds! Finally, the most exciting bird this summer, perhaps, was a return Eastern Wood-Pewee (EAWP). We hear EAWPs singing their heads off every week at Oaks, but this was the first (and only) that we’d had in the nets. And boy, was it a doozy! “It’s just a wood-pewee,” you say, “What’s so interesting about that?” Well, it’s neat partly because we just don’t get that many recaptured or return flycatchers. Secondly, this particular bird was banded as an after-hatching-year (AHY) in 2014, making it at least 10 years old and setting a new longevity record for the species! This is actually the second longevity record that has come from Oaks, the first being a 10-year-old Blue Grosbeak back in 2017.

Species longevity and other population statistics are an important piece of conservation information that can be gained from MAPS banding. For more information about the MAPS program, check out www.birdpop.org/pages/maps. With the breeding bird season now behind us, we're busy getting back into fall migration operations in the Navarre Marsh Banding Station. Here is an initial breakdown of the numbers from this summer: Oak Openings:

BSBO Headquarters:

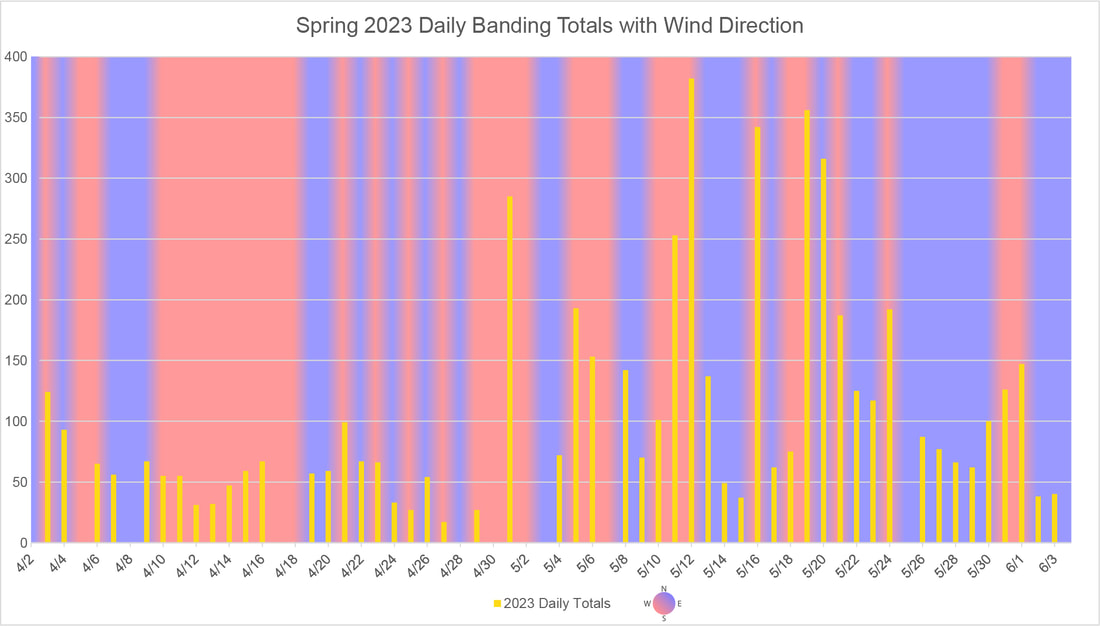

With the spring migration banding season now behind us, we wanted to take a moment to reflect on some of the ups and downs of the past couple months. While every season is unique, overall, it was kind of an unusual season: cold weather and many nights of north and east winds weren't conducive to a normal spring. Our first push of birds, which usually happens at the end of April, was really more of a trickle. Instead of getting days with hundreds of White-throated Sparrows or hundreds of Ruby-crowned Kinglets, we ended up with them spaced out over a much longer period of time. Even Myrtle Warblers (which tend to be a major mover in early spring) had one day of ~180 birds banded, and then a sparse showing following this one push.

Without southwest winds to facilitate movement, birds took their opportunity to migrate whenever they could, rather than coming all at once. This lack of a tail wind combined with northerly winds also meant that birds were more distributed across the landscape, rather than being directed to our part of the lakeshore. But aside from the less-than-ideal wind direction, the season was also unusual in terms of species abundance. On the whole, most warblers were below the long-term average. However, some, such as Northern Parula and Black-throated Blue Warbler, were well above average. But most noticeable in absence were the thrushes. While Hermit Thrushes had a strong and protracted migration (being well above average), the other brown thrushes were all below average. Although Swainson's Thrush ended up not being too far off from average, their lack of presence was continually noted throughout the spring. Typically, we will capture the first Swainson's Thrush in early May, with the bulk of birds traveling through in mid- to late May. But, we didn't capture a Swainson's until May 11, with the busiest day for the species only having 37 birds banded. We actually banded all the other brown thrushes before having a Swainson's!

Aside from the sort of "slow" nature to this spring's migration, we did have some other interesting captures this year. While the station focuses on songbirds and near-songbirds, our nets will capture (but not always hold!) anything that flies. This included a Sora and Solitary Sandpiper this season, neither of which has been banded at the station in a number of years. We were also able to start operations early enough most mornings to capture an Eastern Whip-poor-will and two Eastern Screech-Owls (plus three return screech-owls).

Speaking of returns (birds banded in a previous season), we introduced a new piece of technology to our operations this season: a tablet loaded with the past eight years of banding data to make our recapture recording and age verifications much smoother. With this, we already know that, of our recaptured birds, about 125 were return birds. While most of these birds were from the fall of 2022, many were older with quite a few having been originally banded in 2021 and 2018 and even a couple from 2015. So, while migration may have felt a little "off" this spring, it was still an interesting season regardless. Our goal isn't to capture as many as birds as possible, but rather to document the passage of birds from year to year in a consistent method. Every year (and every individual species) is different; some are high, some are low, and some are average. But, even the slow years allow us to gain critical information that can be used to aid the conservation of those species that pass through this area every spring. While there is much work ahead now on data entry, presented here is a preliminary breakdown of some of the numbers from this season: Total Birds Banded: 5,647 Species Banded: 102 Banding Days: 52 Banding Hours: 268.62 Total Net Hours: 6090.26 Number of Volunteers: 43 Species with New High Records: Tree Swallow - 51 American Robin - 42 Yellow-shafted Flicker - 21 Top Ten Species Banded: Gray Catbird - 468 White-throated Sparrow - 461 Magnolia Warbler - 349 American Redstart - 328 Myrtle Warbler - 294 Ruby-crowned Kinglet - 237 Hermit Thrush - 211 Swainson's Thrush - 200 Yellow Warbler - 191 Common Yellowthroat - 179 For more numbers throughout the season, head over to the 2023 Spring Daily Banding Totals on our Passerine Research Page. We would like to thank our incredible, dedicated group of volunteers and seasonal techs that put all their effort into ensuring a successful banding operation, for both data quality and bird safety. We couldn't do it without all your support!!! We would also like to thank the amazing crew at Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge for their continued support of this project and Davis–Besse Nuclear Power Station and Energy Harbor for preserving and allowing access to this incredible habitat. If you would like to support BSBO's research efforts, please consider our Sponsor a Mist Net program, which directly contributes to our banding programs. Learn more and Sponsor a Mist Net here.  WHIP-poor-WILL, WHIP-poor-WILL! The Eastern Whip-poor-will (EWPW) is often heard but very rarely seen, which is why it was so exciting to catch one in the nets a few mornings ago! Whip-poor-wills are pretty widespread throughout the eastern United States, but their nocturnal habits and highly camouflaged feathers mean that most people can go their whole lives without ever seeing one. It’s even unusual to see one at the banding station; although we open the nets before sunrise, we’re often just a little too late for the whip-poor-wills. Our EWPW was easily identifiable as a female because of the smaller, buffy spots in her outer rectrices. A male would have had large white patches on either side of the tail. In addition to sexing the bird, we were also able to use several plumage characteristics to determine that our bird was an after-second-year, or ASY. One of these diagnostic features is that the rectrices and outer primaries were very broad and truncate instead of narrow and pointy. Another clue is that the primary coverts and outer greater coverts had distinct brown spots with dark edging instead of buff tipping/edging that would indicate a younger bird. EWPW are part of a family of birds known as nightjars, most of which are nocturnal, cryptic insectivores. One other relative, the Common Nighthawk, occurs in northwestern Ohio, but it can be quickly differentiated from EWPW by the presence of white wing patches that are very visible in flight. Like all nightjars, EWPW have large heads, rictal bristles (or “bristicles” as we like to call them), and very soft body plumage. They also have middle toes that are pectinate, meaning that they have little projections, like the teeth on a comb. These specialized toenails are used as grooming tools to brush feathers and rictal bristles. Another fun adaptation of EWPW is their deceptively tiny beaks. Because EWPW are strictly insectivorous, they don’t need very strong beaks. However, since they catch insects while flying, that dinky little beak opens up into a massive gape that allows them to easily gobble up fairly large bugs. Unfortunately, these fascinating birds are not nearly as numerous as they used to be. Habitat loss due to agriculture and urbanization and food source loss due to pesticides are major drivers of the population decline. Additionally, as a ground-nesting bird, EWPW are particularly vulnerable to predation, both from other wild animals and from outdoor cats and dogs. One easy thing that we can all do to help EWPW and other birds is to keep our cats inside. If you’d like to read more on the topic of cats or on what else you can do to support conservation, check out BSBO's Position of Feral and Free-ranging Cats and Easy Ways for YOU to Support Conservation.

Text and photos by BSBO Passerine Research Technician, Yvonne Thoma-Patton There are so many wonderful things about Northwest Ohio. The unpredictable weather is not exactly one of those great things. You may notice a day or two during the season - maybe even three - without a daily update from the Navarre Marsh Banding Station. The last few days of April and the first days in May were a mixed bag of warm, cold, snow, and wind, with on and off rain showers. Our station is required to adhere to USGS Bird Banding Laboratory permit guidelines (the federal administrators of the USA's banding program) and follow the North American Banding Council Banders Code of Ethics. The welfare of the birds should be the most important priority (USGS 2021). Banders should ensure the respect, safety, and welfare of birds and their populations, people, and the environment (NABC 2021). Strong wind, rain, snow, and extremely cold conditions prevent us from opening our station during foul weather. But while we may not process birds on inclement weather days, there are many other tasks we perform! One team member may administer a point count at sunrise, even if we aren't banding. The point count is an inventory of the number of birds both seen and heard from six specified points within the station. The observer counts and logs the number and species of birds within a designated area for a 5-minute period. This standardized data collection method is performed every day we band too and gives an idea as to what species are passing through the area that we may not catch (hawks, ducks, flocks of Blue Jays, etc.). Other team members perform maintenance duties like trimming near pathways and mist net lanes without disturbing the habitat. We reset and replace mist nets, address trip hazards, maintain boardwalks, and perform many other tasks that ensure the safety of the birds, volunteers, and the environment. We also conduct weekly vegetation surveys. The survey involves repeated measurements of the same sample units, to assess changes in vegetation composition, structure, and condition over time. We look at vegetation density at our specified point count locations looking north, south, east, and west; using a ten-foot pole with black and white sections as the visibility index. We compare data weekly and yearly to figure out if climate change impacts foliage growth timing each season. Vegetation growth impedes our ability to observe birds both visibly and by sound, and therefore will have an impact on our point count surveys. As much as we would like to post pictures of the amazing birds that make a pit stop in the Navarre Marsh unit of Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge every day, some Ohio spring days just don’t allow it. There are always a team of staff, field technicians, and volunteers working behind the scenes to ensure this long-term study continues seamlessly.

And... there's always bird bag laundry.  Cold and wet, but still smiling! Cold and wet, but still smiling! Although it may be hard to believe when looking at the weather right now…spring has sprung! We’ve been out in the marsh for a few weeks now, since the very beginning of April, and there’s been a fair amount going on already. We started off by doing some necessary maintenance, and we were very lucky to have some employees of the Toledo Museum of Art come out to help us for a day. They were real troopers and worked through a bit of rain before heading to the BSBO office to help organize some things for Biggest Week. It was very generous of them to donate their time to us, and they really proved that many hands make light work! Our other big, pre-season chore was everybody’s favorite job: boardwalk repair. Luckily, we didn’t replace nearly as many boardwalks as we had to last year; in fact, we only replaced the middle portion of the boards at net 3. Since we’re highly-trained professionals, it only took a couple hours and was (relatively) painless. Staff started running the station on April 3rd, just to make sure we’d worked out the kinks, and volunteers started the following week. One of the most exciting things that has happened so far is that the banding station has entered the 21st century! We may not have electricity in the station, but we do have…drumroll, please…a TABLET!! This may not sound that exciting to the general public, but it’s been incredibly useful for us, so far. It has been programmed to be able to call upon data from the last few years, so, when we recapture a bird, we can get instant feedback as to when that bird was first banded. It’s a great self-check on our aging skills, so we can be sure that we’re aging birds correctly. The tablet will also save us time at the end of the year by making it so that we don’t have to enter all of our recapture data, and it solves a problem that we’ve always struggled with: reading our own handwriting. Speaking of recaptures, we've had some sensational return birds already this year! Return birds are recaptures that were first banded in a previous season or year, and they’re interesting because they’re able to give us longevity information for that species and document site fidelity (the tendency to return back to a specific site). Our first noteworthy return was a male Rusty Blackbird (RUBL), which is already pretty cool, since we don’t catch that many of them. RUBLs have been undergoing a population decline for a while now, but the marsh region seems to be a consistent stopover destination for them during spring and fall migration. This particular bird was banded at the station in 2017 as a second-year (SY) bird, meaning that he was hatched in 2016. This makes him almost seven years old, which is pretty impressive for a songbird (right?)! Our next oldest return bird was a female Hairy Woodpecker (HAWO) that we identified as an after-third-year (ATY) bird. She was originally banded at the station as an SY in 2016, making her almost eight years old. Finally, most exciting of all was a bird that was actually captured by someone else! In the fall of 2015, at Navarre, a male Brewster’s Warbler (BRWA)(the common hybrid between Golden-winged and Blue-winged Warbler) that was aged as an after-hatch-year (AHY), meaning that he had been hatched either the previous year or in an even earlier year. We found out a few weeks ago that that very same bird had been caught in the summer of 2022 by a bander named David Toews during banding operations in Michigan, meaning that he’s at least eight years old (and maybe more)! With no longevity data available, this bird is quite possibly the oldest BRWA on record. All in all, we’ve had a busy season already, and we haven’t even hit the first wave of migration yet!

For more information on the Bird Banding Laboratory's (BBL) longevity records and how bird ages are calculated, please visit the BBL's website HERE. Every season of banding is interesting in its own way. Some years it's really wet, some very hot. Sometimes the winds are perfect, and other times the wind just won't cooperate. And then some years particular species or families are prolific, and then other years all of migration is ho-hum. This was one of those falls where temperatures seemed to stay a bit warmer than usual and winds tended to be out of the south (probably explaining much of the warmer conditions). By the end of the season we ended up banding close to 5,000 birds, which is just above the long-term average for fall (4,780). But most of the action didn't occur until October once short-distance migrants began moving through the region. In fact, we didn't have a 100 bird day until September 27th (one of the latest years to go without a 100 bird day) with the rest of our 100 bird days occurring in October (we never did break a 200 bird day this fall). Owing to this slow start was the lack of long-distance migrants, particularly Blackpoll Warbler, Swainson's Thrush, Gray-cheeked Thrush, and many of the warblers. For many of these long-distance migrants, they weren't significantly below average (except maybe Blackpoll Warbler and Gray-cheeked Thrush), but on the whole, the below average numbers in many of these species made for a slow September. Of special note though were Black-throated Blue Warbler who set a new high record for fall and were 138% above the long-term average. If there had been just a few less Gray-cheeked Thrush, Black-throated Blue Warbler would have cracked the top ten species banded for the first time ever. What led to this influx of Black-throated Blues when nearly all the other long-distance warblers were below average is so interesting to ponder. Was this a regional influx or range-wide? How will this carry over into spring next year? Will we see a dip next year? As alluded to earlier, much of this season's numbers came during October (over half of all this fall's birds were banded in October). Leading the way in October were White-throated Sparrow, Golden-crowned and Ruby-crowned Kinglet, Myrtle Warbler, and Hermit Thrush. Unlike other years, we never really saw a big push of these short-distance migrants on a particular day. In many years, we will get close to 100 (or more) kinglets on a given a day, or White-throated Sparrows, and then they'll peter out after this. Instead, throughout October we would have consistent days of a couple dozen or more of these species. Rather than big pushes, we experienced a steady stream of these short-distance migrants throughout October, leading to many of them being above average. The other very interesting part of this fall was the number of "big" birds encountered. Before the season gained traction in October, we joked that it was the season for big birds. And whoa was it! We banded the first ever Broad-winged Hawk for the station; the fifth ever Red-tailed Hawk for fall; the sixth ever Cooper's Hawk for fall; the third and fourth ever Northern Saw-whet Owls for fall; the second ever Eastern Whip-poor-will for fall; AND... 14 American Woodcock (24% of all the woodcocks we've ever banded in fall were banded this season). While we hoped to continue this trend with a random Red-shouldered Hawk or Northern Shrike (which never came to pass) it was still an incredible season for these non-target species. While there is much work ahead now on data entry, presented here is a preliminary breakdown of some of the numbers from this season: Total Birds Banded: 4,846 (1% above average) Species Banded: 90 Banding Days: 72 Banding Hours: 321.61 Number of Volunteers: 38 Species with New High Records: American Woodcock - 14 Broad-winged Hawk - 1 Northern Saw-whet Owl - 2 Black-billed Cuckoo - 2 Slate-colored Junco - 81 Black-throated Blue Warbler - 112 White-breasted Nuthatch - 7 American Robin - 219 Top Ten Species Banded with % Difference from 1990-2021 Average (green above, red below): White-throated Sparrow - 572 67% Swainson's Thrush - 392 19% Golden-crowned Kinglet - 380 49% Blackpoll Warbler - 374 33% Gray Catbird - 323 11% Myrtle Warbler - 319 9% Hermit Thrush - 273 50% Ruby-crowned Kinglet - 260 28% American Robin - 219 217% Gray-cheeked Thrush - 123 31% For more numbers throughout the season, head over to the 2022 Fall Daily Banding Totals on our Passerine Research Page.

We would like to thank our incredible, dedicated group of volunteers and seasonal techs that put all their effort into ensuring a successful banding operation; for both data quality and bird safety. We couldn't do it without all your support!!! We would also like to thank the amazing crew at Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge for their continued support of this project (both in research and housing for techs) and Davis–Besse Nuclear Power Station and Energy Harbor for preserving and allowing access to this incredible habitat. If you would like to support BSBO's research efforts, please consider our Sponsor a Mist Net program, which directly contributes to our banding programs. Learn more and Sponsor a Mist Net here. With the spring migration banding season now behind us, we wanted to take a moment to reflect on this past season and share some of the preliminary numbers with you. Every spring banding season is a monumental task, but this was our first spring back in full operation since 2019, and we would not have been able to resume this important research without the help and support of numerous individuals and organizations.

We would like to thank our dedicated group of volunteers and seasonal techs that put all their effort into ensuring a successful banding operation; for both data quality and bird safety. We couldn't do it without all your support! We would also like to thank Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge for their continued support of this project (both in research and housing for techs) and Davis-Besse Nuclear Power Station and FirstEnergy Corp. for preserving and allowing access to this incredible habitat. If you would like to support BSBO's research efforts, please consider our Sponsor a Mist Net program, which directly contributes to our banding programs: www.bsbo.org/sponsor-a-mist-net Spring Recap: Navarre Marsh Banding Station Banding Days: 46 Species Banded: 100 Number of Birds Banded: 6,212 Species with Record Highs: Black-billed Cuckoo - 9 Rusty Blackbird - 21 American Tree Sparrow - 48 Brown Thrasher - 24 Top Ten Species Banded: Magnolia Warbler - 440 Myrtle Warbler - 425 Gray Catbird - 381 Traill's Flycatcher - 337 White-throated Sparrow - 322 Yellow Warbler - 266 American Redstart - 237 Common Yellowthroat - 207 Swainson's Thrush - 159 Red-winged Blackbird - 143 |

AuthorsRyan Jacob, Ashli Gorbet, Mark Shieldcastle ABOUT THE

|