Enjoying our blogs?Your support helps BSBO continue to develop and deliver educational content throughout the year.

|

WHIP-poor-WILL, WHIP-poor-WILL! The Eastern Whip-poor-will (EWPW) is often heard but very rarely seen, which is why it was so exciting to catch one in the nets a few mornings ago! Whip-poor-wills are pretty widespread throughout the eastern United States, but their nocturnal habits and highly camouflaged feathers mean that most people can go their whole lives without ever seeing one. It’s even unusual to see one at the banding station; although we open the nets before sunrise, we’re often just a little too late for the whip-poor-wills. Our EWPW was easily identifiable as a female because of the smaller, buffy spots in her outer rectrices. A male would have had large white patches on either side of the tail. In addition to sexing the bird, we were also able to use several plumage characteristics to determine that our bird was an after-second-year, or ASY. One of these diagnostic features is that the rectrices and outer primaries were very broad and truncate instead of narrow and pointy. Another clue is that the primary coverts and outer greater coverts had distinct brown spots with dark edging instead of buff tipping/edging that would indicate a younger bird. EWPW are part of a family of birds known as nightjars, most of which are nocturnal, cryptic insectivores. One other relative, the Common Nighthawk, occurs in northwestern Ohio, but it can be quickly differentiated from EWPW by the presence of white wing patches that are very visible in flight. Like all nightjars, EWPW have large heads, rictal bristles (or “bristicles” as we like to call them), and very soft body plumage. They also have middle toes that are pectinate, meaning that they have little projections, like the teeth on a comb. These specialized toenails are used as grooming tools to brush feathers and rictal bristles. Another fun adaptation of EWPW is their deceptively tiny beaks. Because EWPW are strictly insectivorous, they don’t need very strong beaks. However, since they catch insects while flying, that dinky little beak opens up into a massive gape that allows them to easily gobble up fairly large bugs. Unfortunately, these fascinating birds are not nearly as numerous as they used to be. Habitat loss due to agriculture and urbanization and food source loss due to pesticides are major drivers of the population decline. Additionally, as a ground-nesting bird, EWPW are particularly vulnerable to predation, both from other wild animals and from outdoor cats and dogs. One easy thing that we can all do to help EWPW and other birds is to keep our cats inside. If you’d like to read more on the topic of cats or on what else you can do to support conservation, check out BSBO's Position of Feral and Free-ranging Cats and Easy Ways for YOU to Support Conservation.

0 Comments

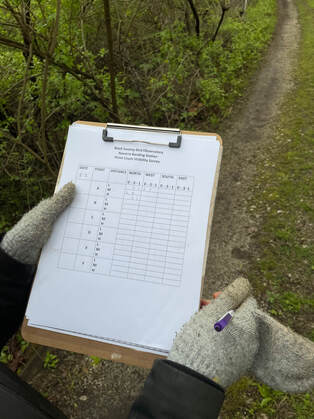

Text and photos by BSBO Passerine Research Technician, Yvonne Thoma-Patton There are so many wonderful things about Northwest Ohio. The unpredictable weather is not exactly one of those great things. You may notice a day or two during the season - maybe even three - without a daily update from the Navarre Marsh Banding Station. The last few days of April and the first days in May were a mixed bag of warm, cold, snow, and wind, with on and off rain showers. Our station is required to adhere to USGS Bird Banding Laboratory permit guidelines (the federal administrators of the USA's banding program) and follow the North American Banding Council Banders Code of Ethics. The welfare of the birds should be the most important priority (USGS 2021). Banders should ensure the respect, safety, and welfare of birds and their populations, people, and the environment (NABC 2021). Strong wind, rain, snow, and extremely cold conditions prevent us from opening our station during foul weather. But while we may not process birds on inclement weather days, there are many other tasks we perform! One team member may administer a point count at sunrise, even if we aren't banding. The point count is an inventory of the number of birds both seen and heard from six specified points within the station. The observer counts and logs the number and species of birds within a designated area for a 5-minute period. This standardized data collection method is performed every day we band too and gives an idea as to what species are passing through the area that we may not catch (hawks, ducks, flocks of Blue Jays, etc.). Other team members perform maintenance duties like trimming near pathways and mist net lanes without disturbing the habitat. We reset and replace mist nets, address trip hazards, maintain boardwalks, and perform many other tasks that ensure the safety of the birds, volunteers, and the environment. We also conduct weekly vegetation surveys. The survey involves repeated measurements of the same sample units, to assess changes in vegetation composition, structure, and condition over time. We look at vegetation density at our specified point count locations looking north, south, east, and west; using a ten-foot pole with black and white sections as the visibility index. We compare data weekly and yearly to figure out if climate change impacts foliage growth timing each season. Vegetation growth impedes our ability to observe birds both visibly and by sound, and therefore will have an impact on our point count surveys. As much as we would like to post pictures of the amazing birds that make a pit stop in the Navarre Marsh unit of Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge every day, some Ohio spring days just don’t allow it. There are always a team of staff, field technicians, and volunteers working behind the scenes to ensure this long-term study continues seamlessly.

And... there's always bird bag laundry. |

AuthorsRyan Jacob, Ashli Gorbet, Mark Shieldcastle ABOUT THE

|