Enjoying our blogs?Your support helps BSBO continue to develop and deliver educational content throughout the year.

|

|

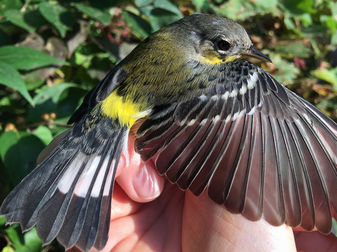

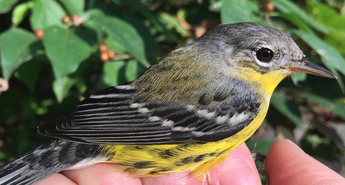

Within a short period of time, we quickly went from banding 20-30 birds a day, to processing 70-100 birds daily. However, with recent hot weather (temps in the 80’s over the past week) our numbers have dropped back down to about 40-50 birds daily. By the end of this week, with temps cooling down and winds coming out of the north, we should really start to see some good numbers as we head into the heaviest part of migration. Our warbler count is up to 24 species now and we have begun to see more diversity in migrants. But the largest bumps in numbers have come from Swainson’s Thrush and Blackpoll Warbler (two of our most dominant fall species), catching (so far) anywhere from 15-40 of each species a day. At this point, Baltimore Orioles and most of the flycatchers have completely left the area, and even though they SHOULD be gone, we have caught a few late Prothonotary Warblers. Along with new thrushes and warblers coming in, we have also banded a few Ruby-crowned Kinglets and a (gorgeous) White-throated Sparrow, and have heard Golden-crowned Kinglet and Red-breasted Nuthatch in the station (sure signs of fall). There have also been a few great surprise captures over the past couple of weeks including a hatching-year (HY) male Golden-winged Warbler. While the mist net mesh size we use is suited best for smaller passerines, we do on occasion catch larger birds (if we can get to them fast enough before they bounce out of the net). Case in point, we were at the nets just at the right time to capture an HY female Cooper’s Hawk this past week. Aging accipiters is pretty straightforward. A yellow eye, brown back, and white chest with vertical brown streaks distinguish this bird as an HY (versus a red eye, blue-gray back, and horizontal orange streaking in an adult). While there is some overlap in measurements between the sexes, determining female from male is also pretty easy, with females being significantly larger than males (this female weighed in at 457 grams). Not necessarily a surprise capture (as we banded a significant amount of them) Magnolia Warbler is a great starter species for learning how to age and sex other Setophaga warblers. First, look for a molt limit in the wing to age the bird. In the bird pictured on the left, there is an obvious difference between the retained narrow, brown-gray juvenal primary coverts (p-covs) and alula, and the newer, black greater coverts (gr-covs); making this bird an HY. The after-hatching-year (AHY)(adult) bird pictured on the right lacks a molt limit, showing similarly colored gr-covs and alula feathers, and wide, dark gray p-covs. Also note the AHY's wide, truncate tail feathers compared to the HY's relatively narrow tail feathers in the lower middle picture. After age is determined, figuring out the sex pretty much comes down to three things: streaks, upertail coverts, and white in the tail. Even in both age groups (HY and AHY), males will typically show more of each of these features than females (ie. more prominent black streaks on the sides, breast, and back, more black in the upertail coverts, and more white in the tail). Looking at our two birds, you can see that the sides have distinct black streaks (especially on the AHY), the upertail coverts are overwhelmingly black, and there are large, similarly sized spots of white throughout the tail feathers (except the center two). Also note the AHY why has some flecks of black in the face. Combined, these three features confidently make the right HY and left AHY both males.

1 Comment

Starting August 14th, the Navarre Marsh Banding Station has been operating nearly seven days a week, sampling migratory birds as they pass through the marshes of western Lake Erie. It’s only been a few weeks, and migration is still quite slow, but boy have we seen some great birds come through the station already! Beginning with a surprise Kentucky Warbler on the first day of banding, so far our warbler list has reached 21 species for the fall season, including Connecticut, Canada, Mourning, Blackburnian, and Chestnut-sided. Not too bad of a start for the beginning of September. Aside from warblers, in our first few weeks we’ve also begun seeing hints of other migrant families represented by Veery, Gray-cheeked Thrush, Swainson’s Thrush, Philadelphia Vireo, and Yellow-bellied Flycatcher. It may seem early in fall migration, but birds are moving, and many of the marsh’s summer breeders have already departed. Yellow Warblers are entirely absent, and Prothonotary’s have become few and far between. Staging Baltimore Orioles are drastically reducing in presence, and Gray Catbirds (abundant only a week ago) are slowly filtering out. But while others are departing, and some are trickling in, flocking species such as Common Grackle and Cedar Waxwing continue to stage along the lake shore, building in numbers every day. While every bird that passes through the station is incredible in its own way, there have been a few birds recently that really caught our attention. The first being an aberrant plumaged Gray Catbird (hatching-year, full juvenal plumage, affectionately termed the Glaucous Catbird) with an apparent melanin deficiency. While most pigment aberrations seem to affect only the feathers on the majority of birds, the interesting thing about this catbird was that every body part color was subdued. Body and flight feathers, beak, legs, and eye color were all a paler color than found on a typical individual. Photographing subtle colors can be difficult, so to try to make the pale color obvious we photographed a normal catbird of the same age shortly after the paler bird in the same lighting. Nearly a week after our first encounter, the pale cat was recaptured with slight signs of body molt. Limited mostly to the crown, the incoming feathers (which would typically be black) appeared to be coming in as a dark brown color. It’ll be interesting to see what this catbird looks like after it completes its molt. Hopefully it’ll stick around a little longer or come back in the spring to offer us a glimpse at its incoming plumage. An unusual visitor for the fall, a hatching-year Olive-sided Flycatcher stopped by this past week, exciting our team and drawing our attention to the plumage characteristics of young flycatchers. Hatching-year flycatchers are easily distinguished from adult birds by the presence of buff tipping to feathers and buff-cinnamon wing bars. This is especially true among the Empidonax flycatchers who show whiter wing bars as adults, in addition to other species who don’t show wing bars as adults, like Eastern Phoebe . For whatever reason, we don’t often see Eastern Wood-Pewees in juvenal plumage, even though it is a local breeder. But the very next day after catching the OSFL, we then caught a hatching-year EAWP, still mostly in juvenal plumage. These two species are members of the genus Contopus, so catching juveniles of each was a great way for us to focus on a new group of flycatchers other than Empids. For a bird that will eventually molt in green-gray feathers, it was interesting to see the extent of buff-tipping to the majority of juvenal body, as well as the wing covert feathers in the EAWP. These buffy wing bars in the EAWP will be white in an adult bird. Also a hatching-year (but further along in molt), the OSFL only showed the slightest edging to remaining juvenal feathers on the back, as well as distinct pale wing bars. These wingbars will be narrow or non-existent in adult OSFL. One very interesting detail we noticed on both of these birds was that the buff/pale edge of these juvenile feathers is even evident at the tips of the flight feathers and tail feathers of both of these closely related species.

|

AuthorsRyan Jacob, Ashli Gorbet, Mark Shieldcastle ABOUT THE

|