Enjoying our blogs?Your support helps BSBO continue to develop and deliver educational content throughout the year.

|

|

While we’re certainly glad to be in a new year, 2021 marked an historic leap for BSBO’s research efforts and our ability to support research occurring across the hemisphere. Amid the uncertainty of COVID, our spring efforts were scaled back to focus on the breeding and migration of Prothonotary Warblers (PROW) in our primary migration research station in the Navarre Marsh unit of Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge. >>>Read more about this ongoing project HERE. This new project utilizes nanotag transmitters and the Motus network of automated radio telemetry towers to track tagged birds following their release. This wasn’t the first time BSBO had deployed nanotags on birds; however, it was our first project as lead investigators, leading to the installation of our first receiver tower. The advantage of these towers and the Motus network is the ability to track not only our birds autonomously, but to detect tagged birds from other researchers and supply them with data necessary for their projects. Even with detailed planning, projects of this magnitude rarely run smoothly the first year. Due to technical difficulties, BSBO's first tower was unfortunately unable to record deployed nanotags in conjunction with our first year of PROW tagging. (We eagerly await the upload of data from other towers in the region to see if tagged Prothonotary Warblers from our site may have spent their summer in other local marshes.) Once we identified the technical issue, BSBO was able to deploy a new radio receiver at our tower in July. Since this deployment (and really since its installation), the Navarre tower has withstood some major storms and wind along the lakeshore and continues to stand strong. So far, the tower has detected 10 tagged birds passing through the marsh, allowing us to document their length of stay. One of these birds was a male Prothonotary tagged during BSBO's PROW project in May, who was detected immediately following the deployment of the new receiver on July 12. This male spent the next 16 days in the marsh until he finally flew off, molted off his nanotag, or until the battery in his nanotag was depleted. Other detected birds were tagged by BSBO in conjunction with a project being investigated by Powdermill Avian Research Center of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pennsylvania. This project is studying the survival and behavior of birds following window collisions. BSBO is the control group, tagging normal, wild-caught individuals. Species tagged by BSBO this fall included Ovenbird, White-throated Sparrow, and Gray Catbird. Following their tagging and release, many of these birds remained in the marsh for 1-4 days before departing. The sole catbird tagged this fall remained at Navarre from October 11 to 14 until it was detected again on October 18 in North Carolina, south of Asheville; a four-day journey of about 440 miles (as the crow/catbird flies). In addition to our own birds tagged this fall, on the night of September 28, an Eastern Whip-poor-will was picked up by our Navarre tower - our first non-BSBO tagged bird detection. This whip-poor-will was originally tagged by Elora Grahame of the University of Guelph in Ontario in August 2021, east of Lake Huron as an ASY (after-second-year, an adult hatched in 2019 or earlier) male. Elora is a Ph.D. candidate focusing on factors affecting migration rate, timing, routes, and stopover duration for Common Nighthawks and Eastern Whip-poor-wills. Elora was generous enough to provide further details about this detected bird and send over photos of him. You can follow Elora and her nightjar updates on Twitter @elora_grahame. Following his tagging in August, this whip-poor-will was detected by towers in southern Ontario by the end of September. Passing outside of Kitchner, London, and St. Clair National Wildlife Area, he would last be detected in Ontario on September 28 on the Point Pelee peninsula before being detected southwest across Lake Erie at our Navarre tower in Ohio. This detection not only exemplifies the collaborative power that the Motus network offers, but also showcases a migration route between Ontario and Ohio and a direct flight over the waters of Lake Erie.

After passing by the Navarre tower, this Eastern Whip-poor-will would not be detected again until October 16 outside of Galveston, Texas on the Gulf Coast. Towers become less prevalent south of this point and are absent from much of the Gulf Coast area of Mexico. So we (and Elora) may not find out where this bird eventually settles for the winter. But we’re both hopeful for his return through our region and to his breeding territory in 2022. With one year of this new technology under our belts we’re excited for what the upcoming year will bring (without technical difficulties!). The Navarre tower will run throughout the winter and plans are in the works to install our second tower south of the lakeshore before spring. The BSBO research department will also be a part of a much larger nanotagging collaboration this upcoming spring migration, so check back soon for future updates! Our sincere thanks to all those who so generously supported this invaluable research.

0 Comments

BSBO breeding bird field work returned to normal in 2021. While the MAPS station was run at Oak Openings in 2020 under strict safety precautions the BSBO station reopened for the first time in two years as water levels returned to lower levels along the lake shore. The summer work did not disappoint as each site held nice surprises and a wealth of information for the long-term datasets. Oak Openings completed its 30th year at the Ostrich Lane site and tallied 174 new birds of 31 species and 35 returns from previous years. Over the seven field dates a total of 26.9 new birds/100 net hours were recorded and 36.1 total birds/100 net hours. Highlights included returning Yellow-breasted Chats (2) and captures of Hooded Warbler, White-eyed Vireo, Blue-winged Warbler, Lark Sparrow, and Red-headed Woodpecker. An exceptional return was made by a Field Sparrow that was originally banded in July 2013, representing a minimum age of 8 years this summer. The BSBO station has been closed due to high water for the past two years so represented almost a new start to field work. This highly productive area nestled in behind the BSBO headquarters building captured 249 new birds of 28 species and 20 returns from previous years. New bird bandings represented 67 new birds/100 net hours and 82.3 total birds/100 net hours in the seven field days. Highlights included Yellow-breasted Chat, American Woodcock, Sharp-shinned Hawk, Eastern Screech-Owl, Yellow-billed Cuckoo, and a late migrating Mourning Warbler. A large number of staging American Robins were encountered on the last field day.

After photographing this Yellow-billed Cuckoo (YBCU) for nearly half an hour, I was flabbergasted when I pulled up the photos on my computer and realized this bird was BANDED! In over 200 photos of this bird, the band showed for only a brief few seconds during the photoshoot owing to short legs and a cuckoo’s propensity for lounging low on a branch. While we’ll almost certainly never be able to read the band number well enough to determine which individual bird this is, the most likely explanation is that this is a locally-breeding, adult YBCU banded by BSBO in a previous year.

There are a few pieces of information that help us reach this conclusion. First, we know that BSBO did not band this bird in 2020, since we haven’t banded any YBCU this year, so if this bird was banded by us, it didn’t happen this year. Second, when we look closely at the band, we can see that the edges have been worn smooth and round, a phenomenon that only happens after (typically) years of wear on a band. This bird was definitely not banded any time recently. So we’re left with two explanations. Option a.) this bird was banded by BSBO in a previous year, or b.) this bird was banded by another bander/banding station in a previous year. In order to parse those options a bit further we need to consider recapture likelihood. “Foreign recapture,” a bird recaptured in a location away from its original banding site, is an occurrence that happens very infrequently in bird banding. A much more frequent occurrence is encountering a “return” bird, one that has been recaptured at the original banding location, but in a season other than that in which it was originally banded. Just considering this likelihood alone, the chance of this bird being a BSBO return is much higher than the chance this is a foreign recapture from another station. One final piece of natural history information helps us even further in our thought investigation. Many species of birds, including YBCU, show some site-fidelity to the breeding grounds, meaning they will return to the same general area year after year to breed, particularly if they have been successful in mating and raising young there. YBCU is a regular breeding bird in the Navarre Marsh and their “kowlp” calls echo through the June beach ridge forests each day once they make their return. While we may never be able to say for sure who this individual is or how old they are, one thing is for certain, the beach ridge habitat in Navarre Marsh is important breeding and stopover habitat for many tens of thousands of birds annually, plus one happy cuckoo. Don't forget to follow BSBO on Facebook where you can stay up-to-date with our daily point counts and join us every Wednesday (about a half hour after sunrise) for Morning Marsh Moments when we go live during our point counts and give a glimpse into BSBO's research station. Typically at the end of the breeding season, our final MAPS update post would occur on the last day of field operations, and contain just that day's banding numbers. But we figured Hey! let's do a MAPS compilation this year like we would with migration. It was another great summer in the Oaks - even with the challenges of living in a socially distanced world - with a few surprise captures and a few questions to dig further into. Conditions were fair throughout the season and the summer heat never seemed to settle in quite as much as other years. Presented below are this summer's initial numbers (having gone through one stage of vetting so far) and impressions from the season.

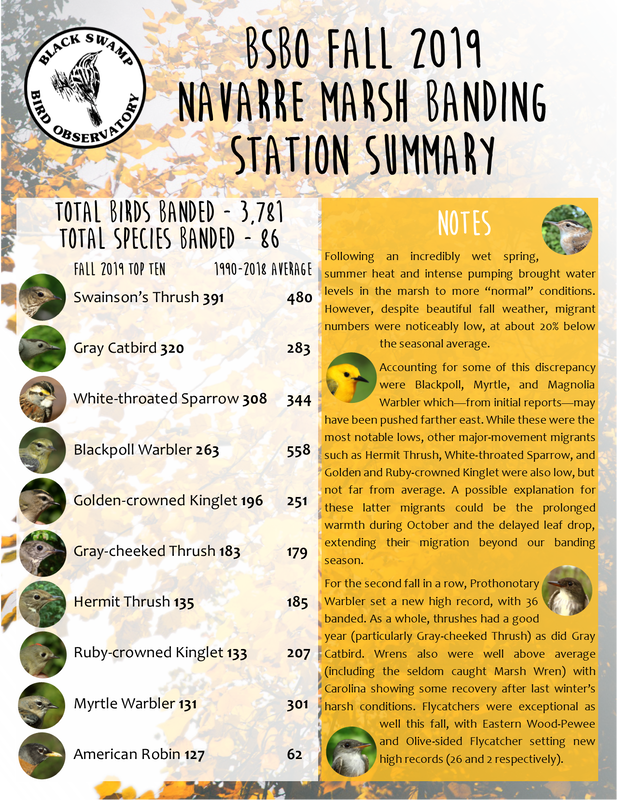

Highlights: Red-headed Woodpecker, Scarlet Tanager, White-eyed Vireo, Yellow-breasted Chat, Mourning Dove, Blue-winged Warbler, and Chipping Sparrow. Although numbers are still initial and have yet to be compared to previous years, this summer felt a little slow and delayed. Numerous causes could have contributed to this feeling including spring weather, habitat management choices, vegetation density and maturity, and just plain 'ol wrong place wrong time; but the timing of peak activity felt to be off by about a week or so. Final analyzed numbers should shed more light on this. But while it may have felt "slow," one species that had an incredible summer was the Yellow-breasted Chat (YBCH). Northern Ohio sits at pretty much the northern extent YBCH's breeding range, resulting in relatively few encounters during migration and summer. Typically, we hope to catch 1 YBCH during banding operations in Oaks, but they appeared to have made quite the eruption this summer with numerous reports throughout the Oak Openings region. 8 being banded this summer exemplifies this surge as this is the highest number we've banded in a single season and represents 31% of the total YBCH that have been banded at the station since 1993 (26 in total from 1993-2020). *Typically we only provide the number of recaptures (a bird banded or encountered within season) in our updates, but we've decided to also include for this compilation the number of returns (birds banded in previous seasons). Among other things, returns can shed light on the number of adult birds returning to a habitat to breed, demonstrate the strength of site fidelity exhibited by a species, and help reveal the longevity of species from numerous years of encounters. For more info on BSBO's research at Oak Openings and the MAPS program, click here. To learn how you can help BSBO's research team and how to adopt a mist net, click here. Thank you to Metroparks Toledo for their support in our research of the birds of Oak Openings and their drive to implement wise and scientifically-based management practices for all wildlife. And THANK YOU to the volunteers that helped us succeed in this project!!! This year, more so than ever, their willingness to help during summer conditions, while also adhering to covid restrictions and best practices, made for safe operations for both people and birds. We would not have been able to do this without them. Again, Thank You! The MAPS program, developed by The Institute for Bird Populations is a continent-wide collaborative effort to assist the conservation of birds and their habitats through demographic and standardized monitoring. Following an incredibly wet spring, a combination of summer heat and intense pumping brought water levels in the marsh to more “normal” conditions. However, despite beautiful fall weather, migrant numbers through the marsh were noticeably low, at about 20% below the seasonal average.

Accounting for some of this discrepancy were our major-movement neotropical migrants – specifically Blackpoll, Myrtle, and Magnolia Warbler – which (from initial reports) may have been pushed farther east this fall. While these were the most notable lows, other major-movement migrants including Hermit Thrush, White-throated Sparrow, and Golden and Ruby-crowned Kinglet were also low, but not far from average. A possible explanation for these latter migrants (which are short-distance migrants) could be the prolonged warmth during October and the delayed leaf drop, extending their migration beyond our banding season. While overall numbers may have been lackluster, there were multiple species that were well represented this season. For the second fall in a row, Prothonotary Warbler set a new high record, with 36 banded, shattering last year’s 26 and going way beyond the average of 8. As a whole, thrushes had a good year (particularly Gray-cheeked Thrush) as did Gray Catbird. Wrens also were well above average (including the seldom caught Marsh Wren) with Carolina showing some recovery after last winter’s harsh conditions. Flycatchers were exceptional as well this fall, with Eastern Wood-Pewee and Olive-sided Flycatcher setting new high records (26 and 2 respectively). Although numbers were mostly low this fall, it is only one season and does not necessarily represent any particular trend. Seasons such as this only stress the importance of long-term monitoring, set protocols, and region-wide collaborations such as the Midwest Migration Network. We would like to thank our dedicated corps of volunteers and seasonal techs that put all their effort into ensuring a successful banding operation; for both data quality and bird safety. We couldn't do it without all your support! We would also like to thank Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge for their continued support of this project (both in research and housing for techs) and Davis–Besse Nuclear Power Station and FirstEnergy for preserving and allowing access to this incredible habitat. Many people visiting the region for spring migration may think that once The Biggest Week In American Birding is over that the birding winds down and the BSBO team finally gets to take a well-deserved break. This, however, is only somewhat true. While it is true that the festival is planned to coincide with peak spring songbird migration, the research team and its volunteers are still out in the marsh daily, collecting data until the first week of June. This year in particular, along with operating one of the nation’s largest banding stations, the research team also accomplished some great feats during spring migration.  Ashli and Ryan examining an affixed radio transmitter on an Ovenbird. Photo by Deven Kammerichs-Berke. Ashli and Ryan examining an affixed radio transmitter on an Ovenbird. Photo by Deven Kammerichs-Berke. Throughout spring, the BSBO research team has been affixing radio-transmitters to particular bird species to monitor their movements after release utilizing the Motus wildlife tracking system (motus.org). These deployments are in collaboration with Powdermill Avian Research Center in Pennsylvania (powdermillarc.org), who are investigating the effects rehabilitated migratory birds may incur after window and building collisions. Acting as a control site for uninjured migrant birds, the BSBO research station was able to deploy 11 transmitters on five species of migrants that are commonly found and rehabbed after collisions along the Lake Erie shoreline (American Woodcock, Wood Thrush, Ovenbird, White-throated Sparrow, and Magnolia Warbler). Once deployed, these transmitters send out a specific radio signature that is picked up by Motus receiver towers positioned throughout North America. When a tagged bird flies within range of these towers, its signature is recorded and uploaded to Motus, allowing researches to see when and where these birds are traveling. Through this collaborative effort the BSBO research team has been able to contribute data to an issue that millions of birds face every year as they traverse the landscape. The information gathered from the movements of these birds will hopefully paint a clearer picture on any immediate or long-lasting effects from collisions and – as an additional benefit – give us a better idea of how migrants are traveling across the lakeshore and Lake Erie. Along with supplying data, this has been an excellent opportunity for the BSBO research team to strengthen its knowledgebase by now including radio telemetry. This is an incredible skillset for us to acquire as BSBO's research and conservation departments begin to explore the Motus system and its application for monitoring birds using the airspace above Lake Erie.  NABC Trainers Ryan Jacob, Mark Shieldcastle, Annie Lindsay, Ashli Gorbet, and Deven Kammerichs-Berke. Photo by Deven Kammerichs-Berke. NABC Trainers Ryan Jacob, Mark Shieldcastle, Annie Lindsay, Ashli Gorbet, and Deven Kammerichs-Berke. Photo by Deven Kammerichs-Berke. While simultaneously operating one of the nation’s largest banding stations, the BSBO research team also hosted a North American Banding Council (NABC) (nabanding.net) certification session, evaluating nine candidates at the levels of Trainer, Bander, and Assistant. The mission of the NABC is to promote sound and ethical bird-banding practices and techniques. To accomplish this, the NABC has developed educational and training materials, including manuals on general banding and an accompanying three-level certification process. While becoming NABC certified is not a requirement to handle or band birds, it is a great accomplishment to achieve and promotes a high standard among bird banders. Two years ago, Ashli Gorbet and Ryan Jacob of BSBO’s research department, achieved the NABC level of Bander. Following that certification, they traveled to Powdermill in 2018 to be evaluated at the Trainer level and attained this status as well. This ranking put Ashli and Ryan among a select group of bird banders recognized as having the skills and knowledge to effectively train and evaluate those in the bird banding community. Coming full circle, Ashli and Ryan (along with established trainers and NABC council members, Mark Shieldcastle and Annie Lindsay, and recently certified trainer, Deven Kammerichs-Berke) were able to take part in hosting a BSBO-led NABC certification session at the end of this past May. Of the nine candidates evaluated, four have exclusively trained with Ashli and Ryan in BSBO’s research station, and were ready for the evaluation process. It was great to have BSBO’s training methods put to the test through this NABC certification session, finding out what we (BSBO’s research team) do well as trainers and what we can still improve on. This has been a significant step forward in achieving one of BSBO’s research goals of training and sending out qualified individuals to the bird banding community. And, with one session now under our belts, the BSBO research team is prepared to continue improving our training methods and hosting certification sessions, hoisting BSBO up among the other great organizations promoting the NABC and bettering the bird banding community. BSBO's Research department continues to make strides in the scientific and banding community for the betterment of habitats and all wildlife. With the support of our partners, volunteers, members, and advocates, the BSBO research team looks forward to a bright future of continued learning, training, and outreach.

Well, after a week of raising our boardwalks out of the drink, last week we were finally ready for the research crew and volunteers to enter the marsh and officially commence banding operations. After being in the marsh for a week prior, we already had an idea of the progression of migration and the species we would catch. But we’ve also had some surprises. This season, more than any in recent memory, has been heavy with Blue-gray Gnatcatchers and we’ve been able to band quite a few. Part of this has been the wind and rainy weather driving them down from the canopy and into the range of our mist nets. Speaking of wind, we’ve also captured an American Kestrel and Sharp-shinned Hawk, who on windy days get forced down from the skies and in range of our nets. As the third week of April began to wane, and Golden-crowned Kinglets and Brown Creepers stopped making appearances, we were in the right time frame to catch some early overflight migrants. These are migrants that typically breed farther south in Ohio, but occasionally get caught up in the overnight winds, overshooting their intended destinations and landing in the lakeshore marshes. Of this group of migrants, we were able to catch a couple of Louisiana Waterthrushes, a Prairie Warbler, and a Pine Warbler (species that are fairly infrequent at the station).

Even though we were catching birds in the double digits, our first real good day of migration came on Tuesday April 23, when winds shifted to the southwest and we had our first 100-bird-day. With this shift, it was almost as if we were in a whole new marsh! We had our first encounters with Eastern Whip-poor-will, Blue-headed and Warbling Vireo, Scarlet and Summer Tanager, Yellow Warbler, Ovenbird, Hooded Warbler, Northern Parula, and Swainson’s Thrush. And not too long after this we also banded our first Gray Catbird for the season. As random as migration may appear, through years of research by BSBO, we’ve been able to identify the pattern of migration through the region, and establish when and which species will arrive. This pattern-knowledge is further strengthened by an understanding of how weather affects bird movement. Using this combination we are pretty accurate with our predictions and have a good idea of what to expect each day we head in to the marsh. Thus, we were pretty sure (ok… we knew) that Tuesday was going to be a good day. What’s neat about this understanding is that it doesn’t take away from the magic of migration in any way. Understanding the factors that drive birds and being able to predict their arrivals and departures reveals a pattern of the natural world, making the spectacle that is migration even more fascinating and awe inspiring!

As we come to the close of April we are hoping that the old saying is true: "April showers bring May warblers." We have had quite a few days of rain and wind hammer northwest Ohio, and are interested to see how persistent northerly winds have affected the progression of migration through the region (especially as we head towards BSBO's Biggest Week In American Birding). Current weather forecasts indicate that Wednesday and Thursday, the 1st and 2nd, could be suitable days for migration; bringing in more Yellow Warblers, Prothonotary Warblers, and Swainson's Thrushes, among others. As long as winter may have felt, the icy winds and snow have quickly faded, and the BSBO research team is back out in the Navarre Marsh, ready to begin operations for the 2019 spring migration season. Well… we were almost ready. With heavy precipitation and strong northerly winds throughout the winter months, the section of marsh the banding station is situated in has been completely inundated by water. We experienced this a bit last year (which aided in catching some of our first-ever Belted Kingfishers), but this year is a whole different level of “flooded.” To best capture birds and sample the movement of different species through the marsh, many of our nets run over boardwalks to get into aquatic habitats such as buttonbush swale. However, the marsh has decided to take these boardwalks for her own and many of them succumbed to the murky waters. For the safety of the birds, volunteers, and staff that work in the station, banding operations could not start until these boardwalks were raised. Thus, a week that could have been spent banding birds and collecting early migration data, was spent waist-deep in the frigid marsh waters, shoving blocks of wood under water-logged boardwalks. Oh what fun! Normally, the research team heads into the marsh a week before our (amazing) volunteers begin coming out. Generally we take this time to get things set up, work out any kinks, and get ourselves back in the groove of banding birds. Not so much this year. Instead we spent four and half days elevating platforms (in some instances, literally elevating the whole thing out of the water), rebuilding some boardwalks, and constructing extensions to span formerly dry areas. As grueling as it was, we had a pretty fun few days getting to know the marsh bottom and the boardwalks a little better; days filled with laughs, sore muscles, leaky waders, and some good ol’ fashion marsh ingenuity. While we weren’t able to operate during this construction time, we did have any opportunity to receive some new training. In collaboration with Powdermill Avian Research Center and others, BSBO will be affixing radio transmitters to certain species this year as part of a project spanning the Lake Erie shoreline. So while we didn’t get to fully operate the station last week, our research team did learn proper techniques for fitting radio harnesses to birds including sizing, actually fitting a harness to a bird, proper tightness, and positioning. Stay tuned for more on this topic as the season develops!  Blue-gray Gnatcatcher Blue-gray Gnatcatcher Finally, after some long, cold days, loads of lumber, and a couple boxes of screws… we were ready to begin banding on Friday the 12th (with the confidence that our feet and nets would stay dry). From being in the marsh earlier in the week, we could already tell from mere observations that there was definitely some good migrant movement occurring in the region. Even though we were a little late to start sampling birds, on Friday and Saturday we were able to catch some remaining Fox Sparrow, American Tree Sparrow, Slate-colored Junco, and Red-breasted Nuthatch. With most of these “winter” birds leaving, others have rapidly been replacing them and the marsh has been filled with the sounds of Ruby-crowned Kinglet, Brown Creeper, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, White-throated Sparrow, and Myrtle Warbler. And while not totally unexpected at this time, with shifting winds going into Saturday, we were happily surprised to encounter an Orange-crowned Warbler, White-eyed Vireo, and House Wren. Similarly to last year (but more so this season), it will be interesting to see how water levels in the marsh will affect bird movement and our ability to catch them in this incredible, ever-changing habitat. One thing’s for sure though… we’re ready to have a great season filled with birds, friends, and new opportunities to learn more about the wildlife we study, and how we can continue to apply our research to conservation. Thank you to all those that make this important research possible by volunteering your time, supporting BSBO and its efforts, and promoting science and conservation.

Due to oncoming thunderstorms, rain, heat, and about 150% humidity, our MAPS banding operations at BSBO were cut short a little bit early today. From the little time we did band, however, we were able to gather that more young Yellow Warblers are on the move with their parents, there are already some completely molted (into formative plumage) hatching-year (HY) YEWAs roaming around on their own, and young Gray Catbirds are just starting to leave the nest, still in their complete floofy juvenal plumage. But our best surprise this morning was a bird we don't often have at BSBO during the summer....American Redstart.  Without catching young or locating a nest, we can't positively say that AMRE have bred at BSBO this summer. The more likely scenario is that this (and other AMRE we've heard this summer and past summers) are simply un-mated birds moving through the region, or birds that have already fledged young somewhere else and are preparing for migration. Unlike migration banding, summer banding offers us a glimpse of birds in active molt - a fairly short period in a bird's life cycle. But due to the plumage differences in male AMRE, this bird's molt was exceptionally interesting! Male AMRE have delayed plumage maturation, meaning that HY and second-year (SY) birds look completely different than their adult counterparts. In AMRE, young males are gray with yellow accents, gaining minute black splotches by their first spring. Whereas adult males are black with orange accents. This plumage difference always makes aging adult male AMRE simple: if the bird is black and orange in spring, it's an after-second-year (ASY); if its black and orange in the fall, its an after-hatching-year (AHY). During the pre-basic molt in late summer, young males will begin replacing their gray and yellow feathers for black and orange feathers, producing the bird's definitive basic (or adult) plumage. The bird we captured today is undergoing that molt right now, showing off a very unique look during this transitional phase.  While in active molt, an accurate age can often be difficult to discern, and sometimes we simply have to say that it's an AHY bird (we don't know when it was hatched, but it wasn't this year). But despite being in active molt, due to the species' delayed plumage maturation, we were able to confidently age this male AMRE as an SY (a bird hatched last year). Black feathers in the head, tertials, greater coverts, primary coverts, inner primaries with orange, and rectrices are all recently replaced, basic feathers. The remaining gray/brown back and face feathers, secondaries with yellow, alula, and outer primaries are retained juvenal feathers (formative for the body feathers). If this were an ASY male AMRE, he would be replacing basic feathers for new basic feathers...black and orange feathers, for new black and orange feathers. Due to the obvious difference in feather ages, our fingers are crossed that this scruffy lad will stick around the area long enough for us to reacapture him and track his advancement in molt, documenting this often unseen and short lived period. In another week or so, this bird will look completely different than today. Gaining all black feathers with orange accents. Because of the timing of this capture, we've added another point of information to the record of this bird, and subsequent recaptures will keep track of his exact age. And, while he may look a "hot mess," isn't this guy just too cool looking!?

As we continue to gather and analyze the data from this year's spring banding season, we've been hard at work operating two MAPS stations: One located in the restored oak/dogwood shrub-scrub habitat along the Gallagher trail behind the BSBO headquarters. And the second, in a portion of the Oak Openings Preserve Metropark that encompasses sand dune, oak forest, shrub-scrub, and degraded grassland habitats. We are about mid-way through the summer season and have encountered some great birds at both stations including American Woodcock, all the Yellow Warblers at BSBO, Cedar Waxwing, Summer Tanager, Ovenbird, and Lark Sparrow. This is such a great and unique time to work with birds - for a multitude of reasons - but chiefly: compared to migration, the return rate of breeding birds is much higher, allowing us to compare individuals from year to year and hone our aging and sexing skills; and both young and adult birds are molting, allowing us to document the patterns of species and the irregularities of individuals. While we would love to write something about each species (and sometimes each bird!) we encounter during the breeding season, there simply isn't enough time or available space on the server to allow for such lengthy posts. However, a few birds each session always tend to catch our eye.  This HY Yellow Warbler banded June 25th at BSBO, has recently left the nest and is still in nearly full juvenal plumage (or first-basic plumage). This first set of body feathers (not often seen in the field) is grown quickly after hatching, providing the young bird with just enough protection and camouflage while it remains in and near the nest. The quality of these feathers is quite low, giving the bird a matte and floofy appearance. After fledging, HY birds will quickly roll into their pre-formative molt, replacing their body feathers and some wing covert feathers (depending on the species). In the case of Yellow Warblers, HY birds will attain higher quality yellow body feathers in their pre-formative molt, giving them the distinct look of the species and separating their plumage as male or female. Because flight feathers are of heavier construction and require more energy to grow (compared to body feathers), many HY birds (including the majority of species of passerine) will retain their juvenal primaries, primary coverts, secondaries, and rectrices through the pre-formative molt, eventually replacing them during the pre-basic molt the following year.  Caught together at Oak Openings, this (presumed) family group of Tufted Titmouse represent three generations of birds. From left to right we have a third-year male TUTI, an HY TUTI (the presumed offspring), and a second-year female TUTI. Despite being quite similar in appearance, the HY bird is still in full juvenal plumage, showing loose, floofy body feathers, a yellow gape, and a pinkish bill base. Male and female TUTI are identical by plumage, and males will develop a brood patch, making it difficult to sex individual birds. Luckily, these birds were captured together and we were able to differentiate physical breeding signs between the two adult birds, separating them as male and female. Due to the nature of molt, we are only able to accurately age most species of birds we encounter into their second year (as most birds will replace all of their feathers at the end of their second summer, showing a single generation of feathers). The adult male TUTI however, was a recapture, previously banded as a hatching-year bird in 2016, putting him in his third-year of life. Without having been previously banded we would only be able to call him an after-second-year bird (a bird hatched prior to last year), based on his feathers. His feathers can only tell us that he's at least older than a second-year, but his band and the associated data can give us a picture of his movements and life at the Oak Openings station.  Captured the same day at Oak Openings, these female Indigo Buntings are almost blue enough that they might be considered SY males if viewed in the field. But, like other sexually dimorphic birds, as female INBU age they will take on plumage characteristics of males, attaining splotches of blue body feathers and blue wing feathers. Individual variation, however, can trump logic (ie it isn't necessarily true that older females will be bluer). The top female INBU shows quite a bit of blue in the crown, along the breast, the lesser coverts, and mid-way through the greater coverts. The bottom female INBU shows extensive blue throughout the crown and nape, along the breast, some of the lesser coverts, the majority of the median and greater coverts, and the undertail coverts. Interestingly, the top INBU is a seventh-year bird (banded in 2013 as an SY), and the bottom INBU is a third-year bird (banded in 2017 as an SY). Banding as a tool can teach us many things about birds such as the longevity and the return rate of individuals to a specific location. In this case, we were able to compare plumage characteristics based on known-age birds, and document the variation of these characteristics between individuals. |

AuthorsRyan Jacob, Ashli Gorbet, Mark Shieldcastle ABOUT THE

|