Enjoying our blogs?Your support helps BSBO continue to develop and deliver educational content throughout the year.

|

|

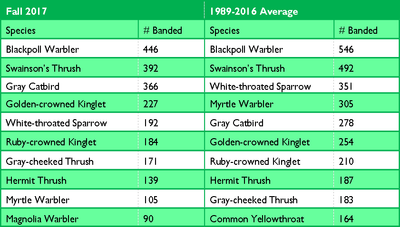

It’s always interesting to reflect on the banding season once the nets are down and the station is closed up. Each season in the Navarre Marsh is unique, with shifting weather patterns; variations in productivity (number of young produced) between species and even within a given species’ range; minor differences in our banding effort (despite our best attempts to be consistent in this regard); and changes in the microhabitat and overall habitat at our banding station driving annual differences in capture numbers. All of these factors and many more can affect species composition, age and sex ratios, and the timing of the birds we capture. While our capture data vary to some degree between seasons, by banding birds consistently over the long-term we can begin to smooth out the extreme highs and lows in these numbers and better understand overall population trends, as well as variables that affect these trends. People often envision wildlife populations as stable year after year, but they can more accurately be described as being cyclical and variable around averages or means. As opposed to the idea of consistent homeostasis, a flat line if you will, bird populations are oftentimes better visualized as a dynamic equilibrium, with near continual change – boom and bust cycles that portray population numbers in a wave-like pattern with highs and lows. Across decades, we can also pick up on overall population increases or decreases, age or sex ratio changes, alterations to arrival or departure timing, and other demographic, temporal, or spatial fluctuations. Teasing apart these factors and their effects are topics we’re looking forward to discussing in future blog posts. For now, we’d like to present some of the interesting trends we noticed during the fall season and discuss them in a slightly broader, historical context.  Yellow-bellied Sapsucker We never catch a lot of these birds during the fall season. In fact, our highest number of captures in a given season is 19 individuals. On average, we band around five Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers each fall. This year, we were close to that average and only slightly above it with six birds banded. What is interesting about this is that last fall (2016) we didn’t band any of these birds. They may have moved earlier in the season (oftentimes birds that fail to breed in a given season will begin to wander or migrate earlier than birds who are tied up in their territory later in the season tending to their young), bypassed our banding station completely, or been present but not captured. With a species that we catch so few of, it’s hard to say exactly what drives these annual differences in capture rate, but in and of itself it’s interesting to merely observe that variability. One way of better understanding the population trends for a species such as this is to compare our annual capture rate with other banding stations over the long term. If capture rates for everyone are down in a given year and everyone’s rates rise in the same year, we can probably safely say that these birds are cyclical in their population trends. Discrepancies in capture rates between stations might indicate more regional or station-specific nuance to bird movements.  White-throated Sparrow Along with Swainson’s Thrush and Blackpoll Warbler, White-throated Sparrow is one of the poster-children of fall migration in the Navarre Marsh. On average we band approximately 350 of these dapper sparrows each fall, but the last two falls have seen us capture far fewer birds than normal with 192 banded this fall and only 158 banded in 2016. These significantly lower numbers could have to do with net height (nets too high off the ground can fail to catch these birds which tend to move close to the forest floor), too many mornings with delayed starts (sparrows are often most active right after dawn, with activity tapering off as the morning goes on), or true population declines. It’s likely that all of these factors are at play to some degree at our station over the last few seasons. Ensuring our banding protocol is consistent and standardized helps us control variation in our effort that may translate to lower catch rate and ensures that the number of birds captured better reflects the true number of birds in the marsh on a given day or in a given season.  Blackpoll Warbler Over the last few seasons, we’ve observed a classic cyclical pattern in Blackpoll Warblers, which is typically the species that helps drive our overall numbers each fall season. In an average year, we band around 546 Blackpoll Warblers. We were down from our average approximately 100 birds with 446 banded in fall 2017. Last year, in fall of 2016, we were well above average with 783 individuals banded. Differential productivity in a species that is very prone to population fluctuations in response to spruce budworm outbreaks, a major food source for these birds on their breeding grounds as well as unusual weather patterns, particularly for a species with the capacity to move huge distances in a short period of time, likely explain at least some of the annual variation in our catch rate. With such a large proportion of the world’s population of Blackpoll Warbler moving through the Lake Erie marshes region each fall, maintaining and improving our stopover sites as well as continuing to track this species each year is essential for helping us unravel migration mysteries and overall population trends for Blackpoll Warblers. It’s also critical for ensuring the protection of this species into the future.  Gray Catbird This species dominates captures during the early part of the fall season each year. Typically, the peak time for Gray Catbirds in our nets is during the month of August, with numbers tapering off throughout September. With our milder-than-usual fall weather as well as less-than-ideal southwestern migration winds during the bulk of September, we recorded Gray Catbirds at the station all the way up until the last week of the banding season in October. We also captured more Gray Catbirds this fall (366) than our average catch of 278 in a given fall. Numbers of Gray Catbird were also up in fall of 2016 with 343 Gray Catbirds banded. Continued tracking of this species over the long term will help us understand if this represents an actual increase in Gray Catbirds overall and how our local productivity may play into our annual fall capture rates. Because Gray Catbirds nest locally and also migrate through our station, timing as well as plumage characteristics might help us separate out how productive our site is for this species and how productivity in our local area affects overall catbird catches each fall. The above cases represent only a few of the trend patterns we observe in the birds we study and some of the factors that may affect these species each fall. The importance of tracking these birds consistently, annually, and over the long term cannot be overstated for helping us understand how overall bird populations are faring and what factors affect bird populations. Banding birds gives us reliable and extensive empirical data to this end, data that surveys or field observations cannot provide. By combining our banding effort with consistent survey results, our data become even stronger and more robust, and paint a better, truer picture of fluctuations and trends in the bird populations we so dearly care for. It becomes an essential piece of the conservation puzzle, as only when armed with this basic information can we begin to open the door to conversations about bird conservation.

As we reflect back on another successful fall banding season we give thanks to the birds that provide us a window into the health of our ecosystems and serve to lift our spirits. Scientifically and spiritually, birds take us to new heights and no matter how many Red-winged Blackbirds we see or how many Swainson’s Thrushes we have the privilege of examining up close, we never lose sight of how important these individual birds are to birders, researchers, and the ecosystems we work to protect.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsRyan Jacob, Ashli Gorbet, Mark Shieldcastle ABOUT THE

|